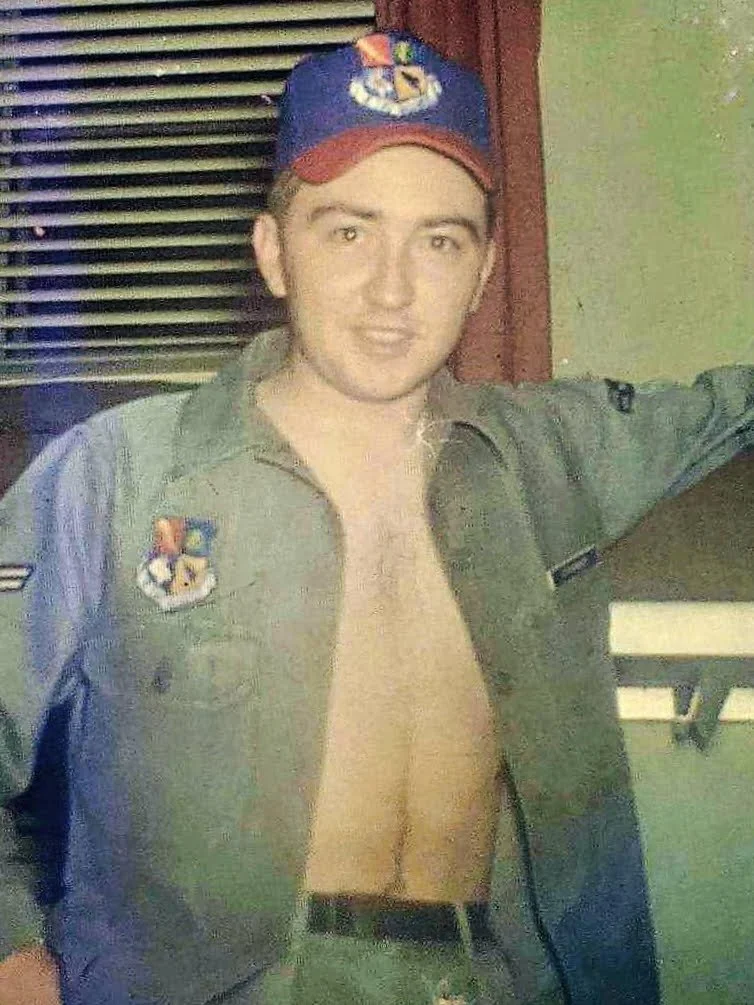

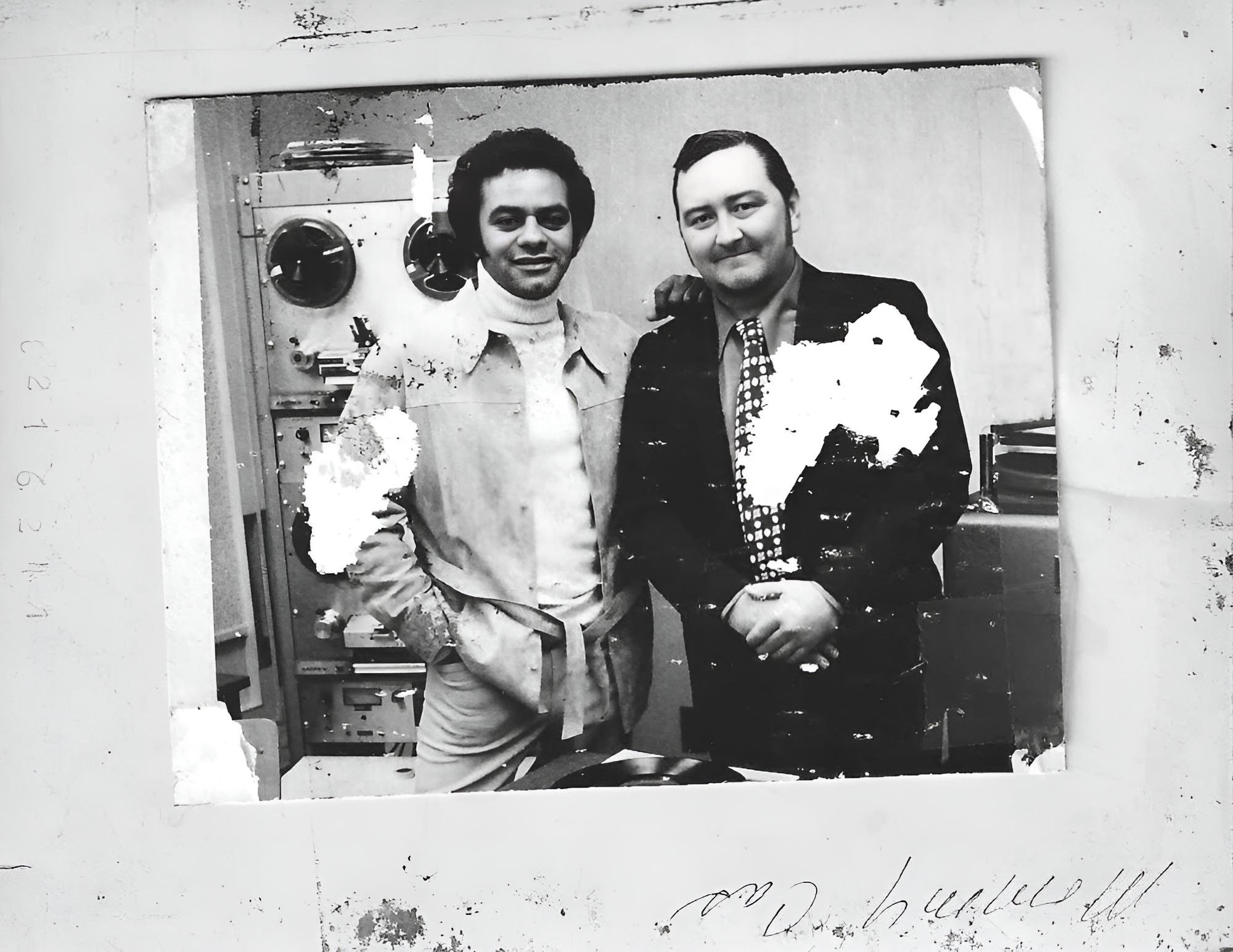

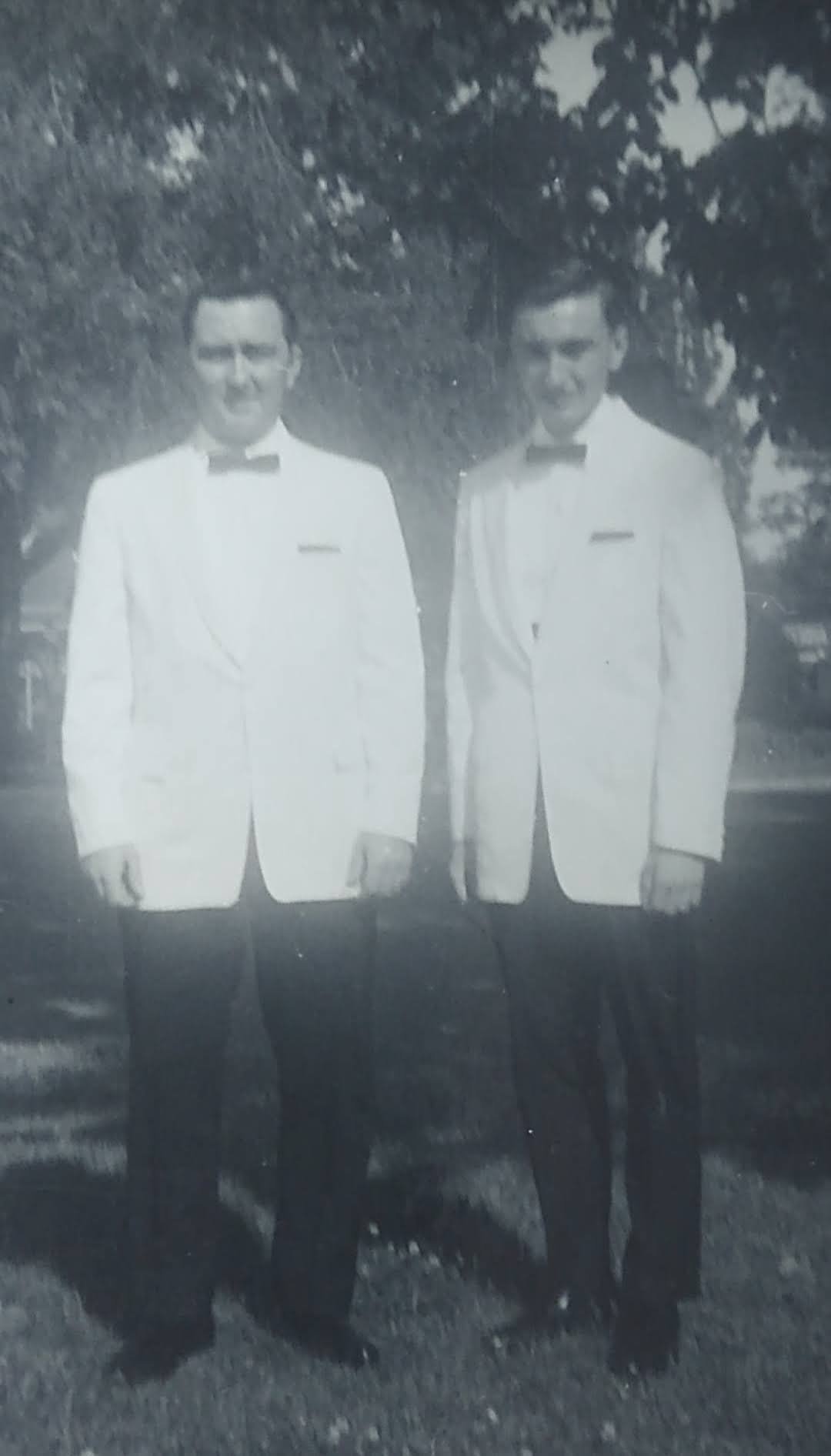

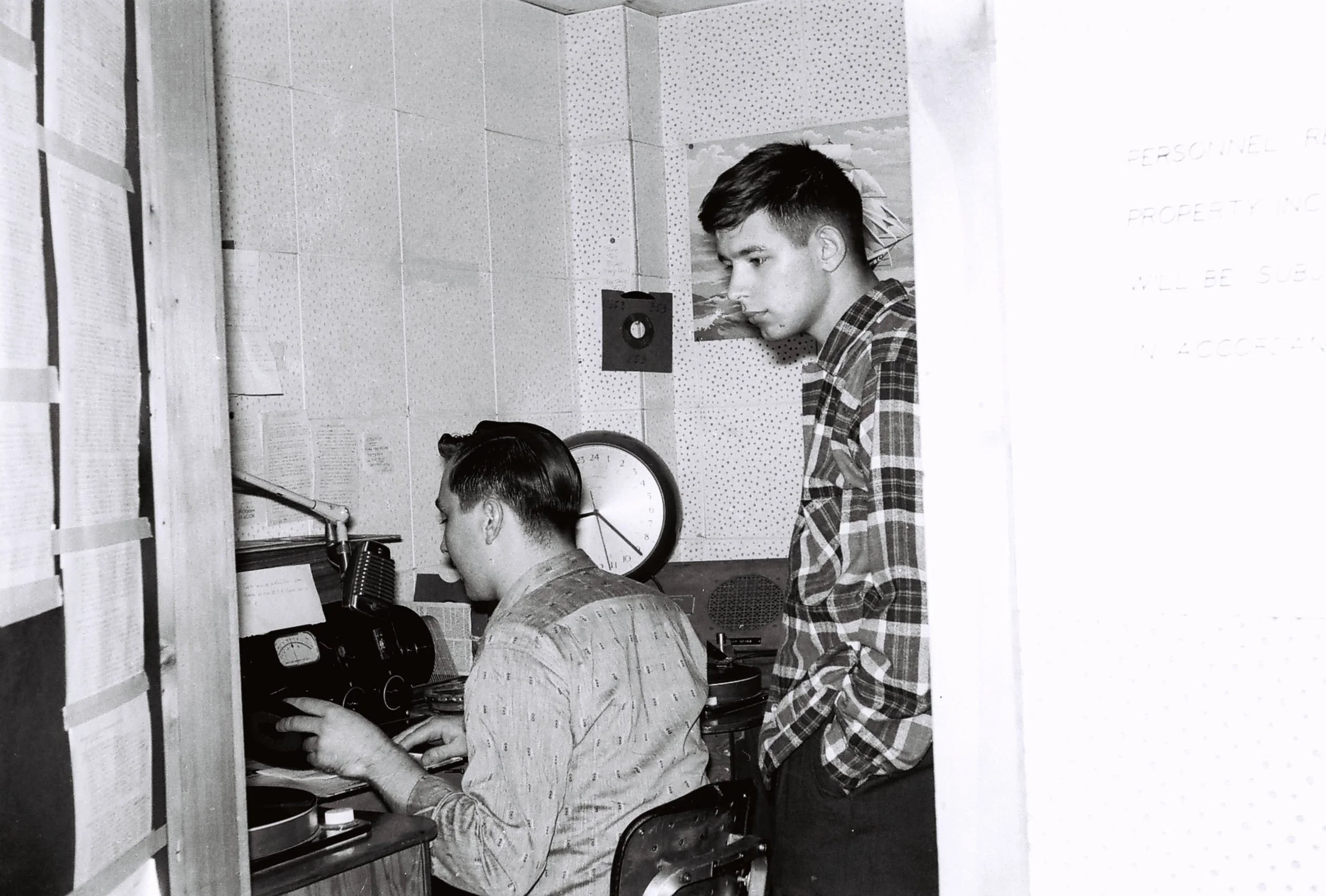

JC - USAF Base, Karamusal Turkey

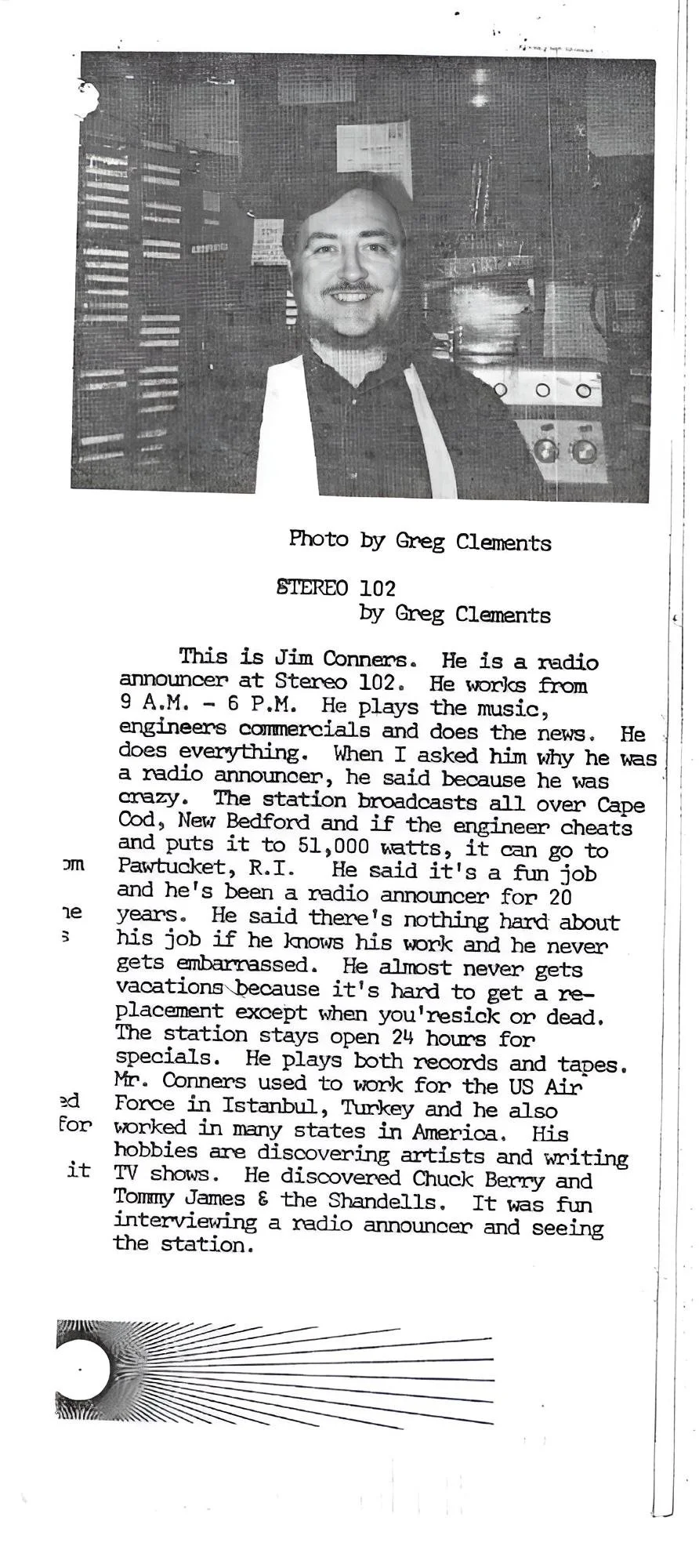

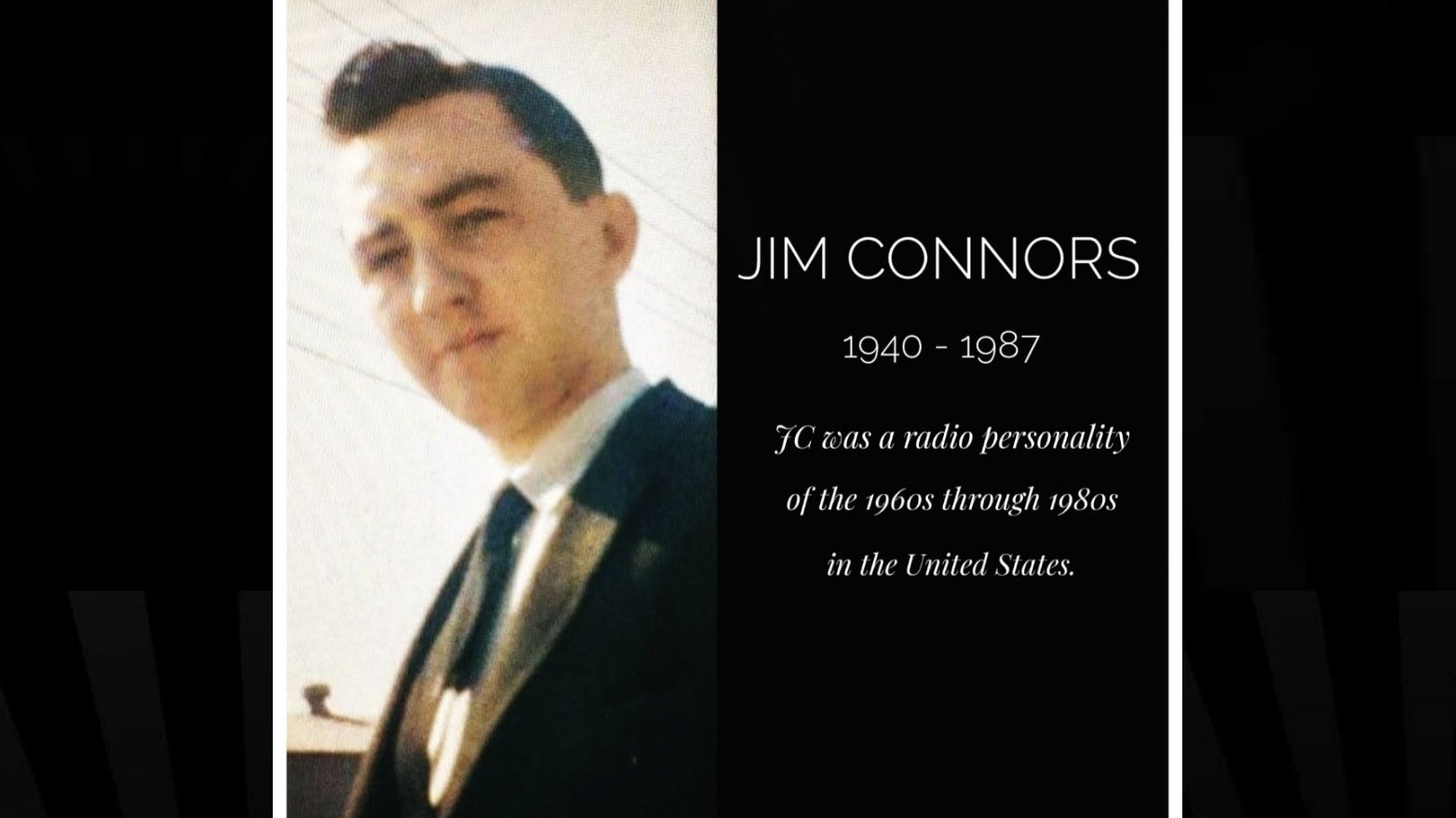

Jim Connors: An Influential Radio Personality in 20th Century Pop Music Culture

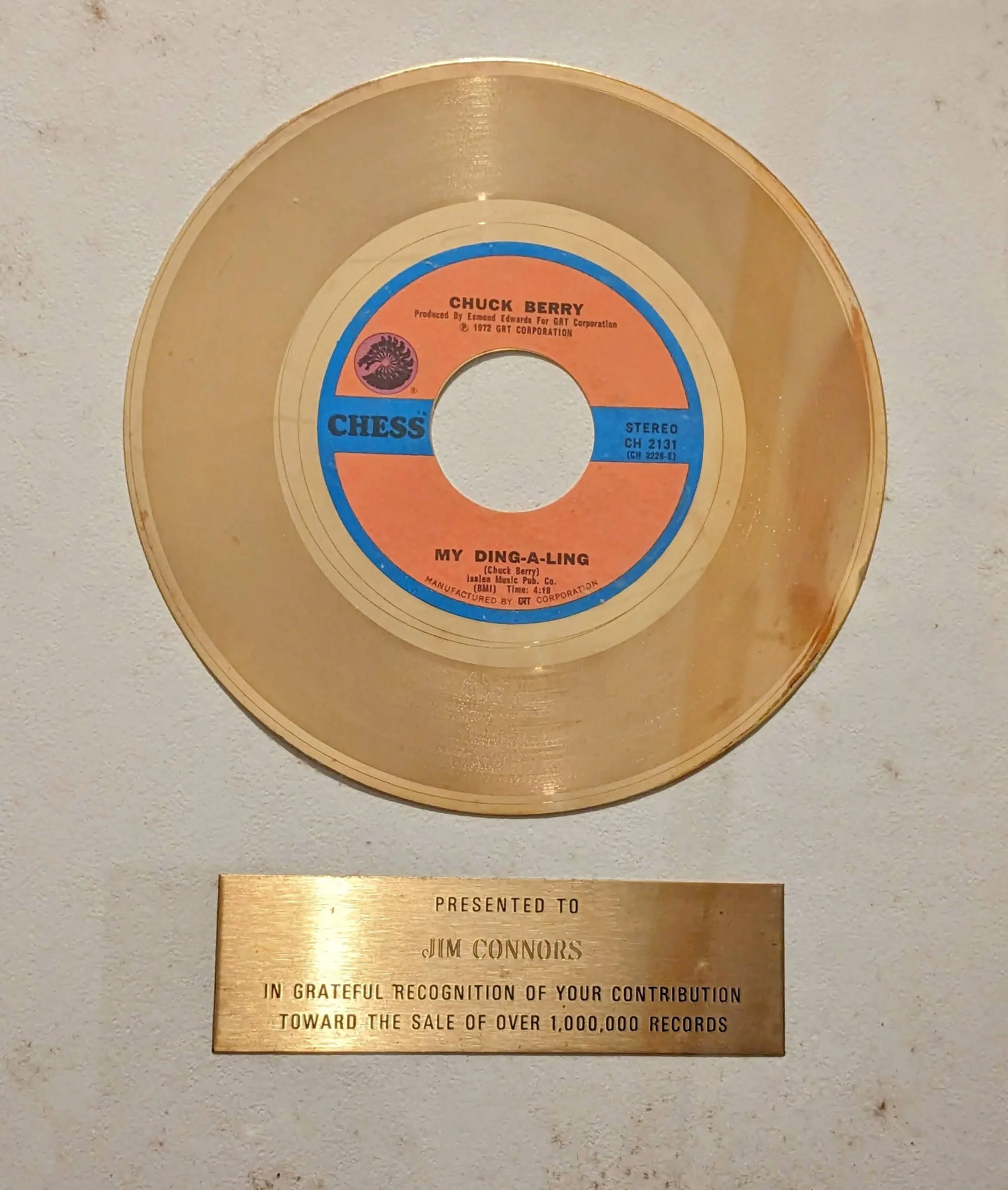

JC was a pioneering radio personality whose voice and instinct for talent helped define popular music in the twentieth century. He played a pivotal role in bringing new sounds to the airwaves, and his influence elevated the careers of artists who went on to sell millions of records worldwide. Along the way, his work was tied to thirteen gold records—an honor that at the time marked sales of 500,000 units in the United States or 100,000 units in the United Kingdom. Those milestones were connected to names that became part of popular culture itself: Tommy James and the Shondells, Blodwyn Pig, Mouth & MacNeal, Chuck Berry, Chi Coltrane, Wayne Newton, Joe Simon, Clint Holmes, Harry Chapin, and Jim Croce.

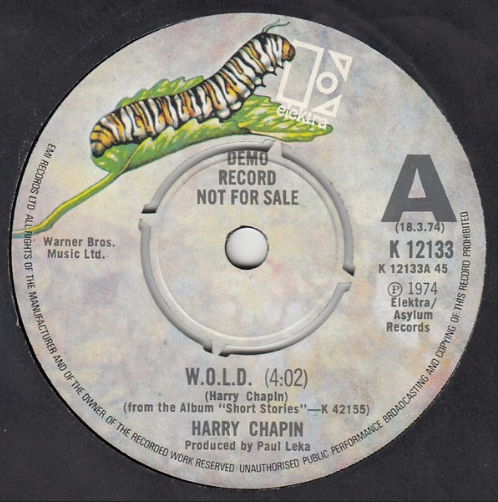

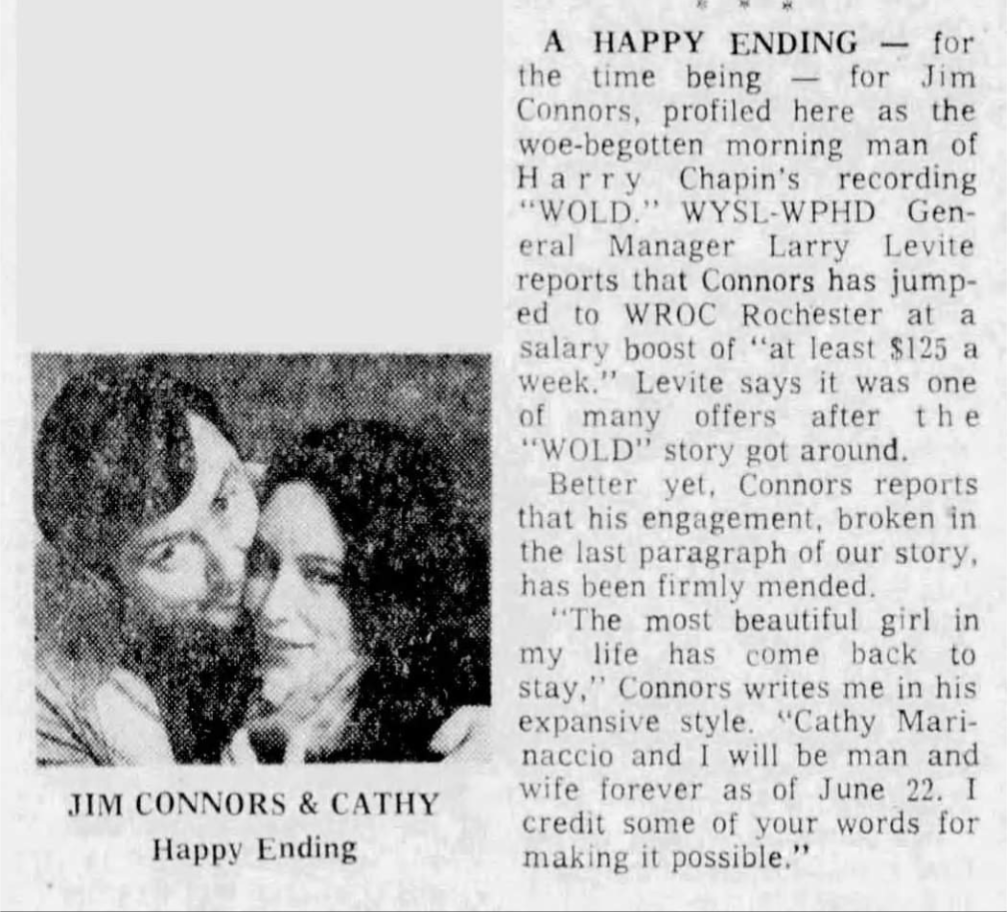

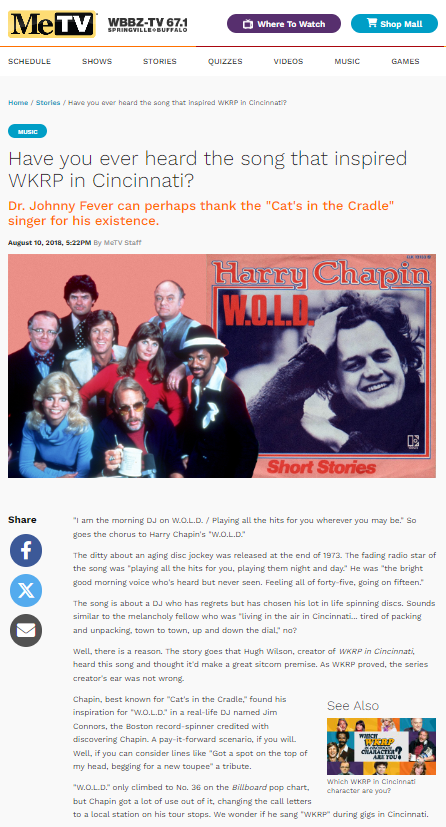

His career in broadcasting even inspired Harry Chapin’s song “W.O.L.D.,” which later became the creative spark for the television series WKRP in Cincinnati. Beyond music, his distinctive voice carried into homes across the country through commercials for Marx Toys, weaving him into the everyday fabric of American life.

JC’s name stands with those who shaped the sound of a generation. His impact on music and broadcasting was measured not only in records sold but in the careers launched, the stories told, and the cultural moments that continue to carry his mark.

1958: JC Graduates from Pawtucket West High School.

In the late 1950s, Pawtucket, Rhode Island, stood as a busy industrial hub, driven largely by its textile mills and related manufacturing. The steady flow of industrial jobs supported a strong local economy and shaped a community that balanced the pace of city life with the familiarity of suburban neighborhoods. Pawtucket’s population reflected a broad cultural mix, with large numbers of French-Canadian, Irish, and Portuguese families contributing their traditions, language, and identity to the character of the city.

Pawtucket West High School, founded in 1895, was one of the city’s central institutions. For students, graduating from Pawtucket West in 1958 represented more than just finishing classes—it was the completion of a disciplined education in English, mathematics, science, and history, coursework designed to prepare young adults for both higher education and steady work in Rhode Island’s industrial economy.

The social life of Pawtucket teenagers in that era often revolved around the school itself. Sports, dances, and assemblies were regular highlights, while community spaces such as Slater Park gave students a place to gather outside of classrooms. Together, these activities reflected not only the traditions of Pawtucket but also the broader patterns of mid-century American youth culture, where education, recreation, and community ties were woven closely together.

This moment in time was also significant because it marked the closing chapter of Pawtucket’s peak industrial years. By the early 1960s, textile production that had sustained the city for generations began to decline, as mills closed or relocated to the South and overseas. The late 1950s therefore carried a sense of stability and prosperity that would soon give way to economic and social change, making the class of 1958 part of the last generation to come of age during Pawtucket’s height as a manufacturing city.

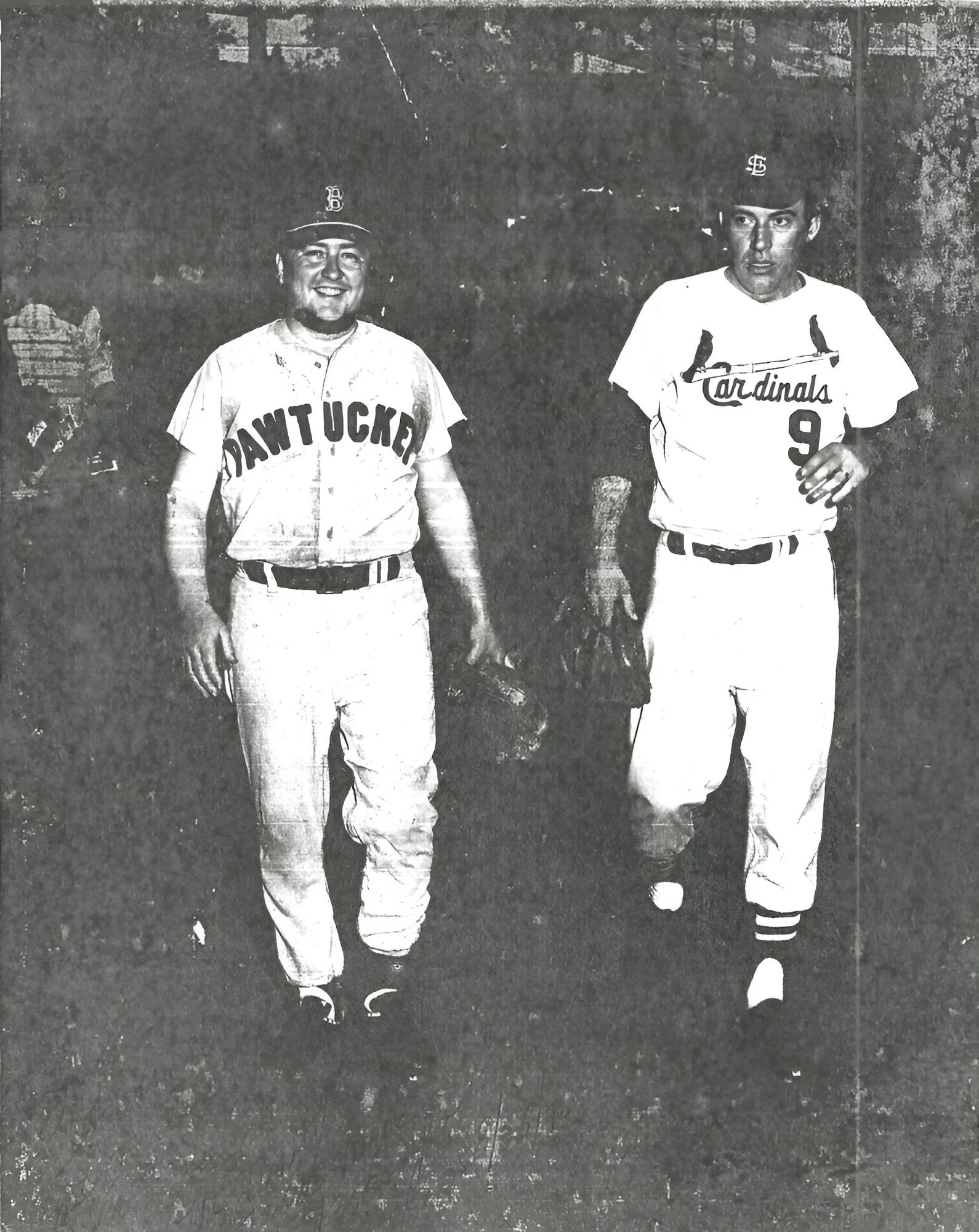

For JC, high school was inseparable from his love of baseball. He played on his school’s team with enthusiasm, finding both competition and camaraderie on the field. That passion carried into adulthood, where he followed the Pawtucket Red Sox and their major league affiliate, the Boston Red Sox. Baseball was more than a pastime; it was a constant thread in his life, tying him to his community and region.

The 1950s offered a backdrop of American prosperity, a trend reflected in Pawtucket’s growing suburbs and steady local economy. At the same time, the nation was beginning to grapple with profound social change, as the civil rights movement gained momentum and prepared the ground for the upheavals of the 1960s.

Graduating from Pawtucket West High School in 1958 placed JC at the threshold of this new era. Like many of his peers, he chose a path of service, enlisting in the United States Air Force in 1959. At that time, the Cold War was intensifying: the Korean War had ended only six years earlier, the Soviet Union had launched Sputnik into orbit in 1957, and nuclear strategy had become central to U.S. defense planning. Joining the Air Force in this climate meant stepping into a world defined by rapid technological change, international tension, and the ever-present possibility of global conflict.

For JC, military service was more than a duty—it was a passage from the familiar mills and neighborhoods of Pawtucket into the broader sweep of world affairs. It placed him in the company of young men facing the same uncertainties of the nuclear age, while giving him skills, discipline, and perspective that would later shape his career in broadcasting. His enlistment marked the first step in a journey that carried him from Rhode Island to the national stage, bridging local roots with a life that would ultimately leave its mark on American culture.

1959: JC serves in the United States Air Force

In 1959, leaving Pawtucket, Rhode Island, for the United States Air Force meant entering a world of discipline and global tension. Basic training provided the foundation: physical conditioning, weapons practice, drill work, and the strict protocols that defined military life. From there, JC’s aptitude carried him into a highly specialized path at the center of the Cold War.

He was chosen for advanced Russian language study, a skill urgently needed to monitor and interpret Soviet military communications. This assignment brought him into the Air Force Security Service, a command whose work remained largely invisible to the public but directly informed America’s defense planning. At Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas, JC trained to intercept and analyze radio transmissions, learning to catch faint signals, record traffic, and detect patterns. He also worked in what was then called Transmission Security, later Communications Security, reviewing U.S. communications for mistakes that could expose classified operations.

After training, JC was assigned to Karamürsel Air Station in northwestern Turkey, a site chosen for its vantage point on the Black Sea and its proximity to the Soviet Union. Turkey was NATO’s southeastern stronghold, and Karamürsel became one of the most important listening posts of the era. JC served with TUSLOG Detachment 3 as part of Dog Flight, one of several rotating crews that kept receivers active day and night. Inside the intercept rooms, rows of operators sat with headphones pressed tight, surrounded by the steady hum of receivers and the faint crackle of shortwave static. Out of the noise came clipped Russian voices from Tu-95 “Bear” and Tu-16 “Badger” bomber crews, or coded exchanges from Black Sea Fleet warships slipping through the Bosporus. Every fragment of sound was logged, translated, and passed up the chain. Reports from Karamürsel went directly into NATO and Pentagon briefings, giving Washington and Brussels a real-time picture of Soviet activity.

The timeline of events underscored the importance of the work. In May 1960, when Francis Gary Powers was shot down in a U-2 reconnaissance plane after leaving Incirlik Air Base, stations like Karamürsel were already tuned to Soviet reactions. In 1961, as the Berlin Crisis unfolded, Soviet bomber patrols and naval traffic became early warning signals. By 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, intercepts from Turkey offered vital insight into Soviet fleet readiness and air operations, feeding into the decisions that kept the world from nuclear war.

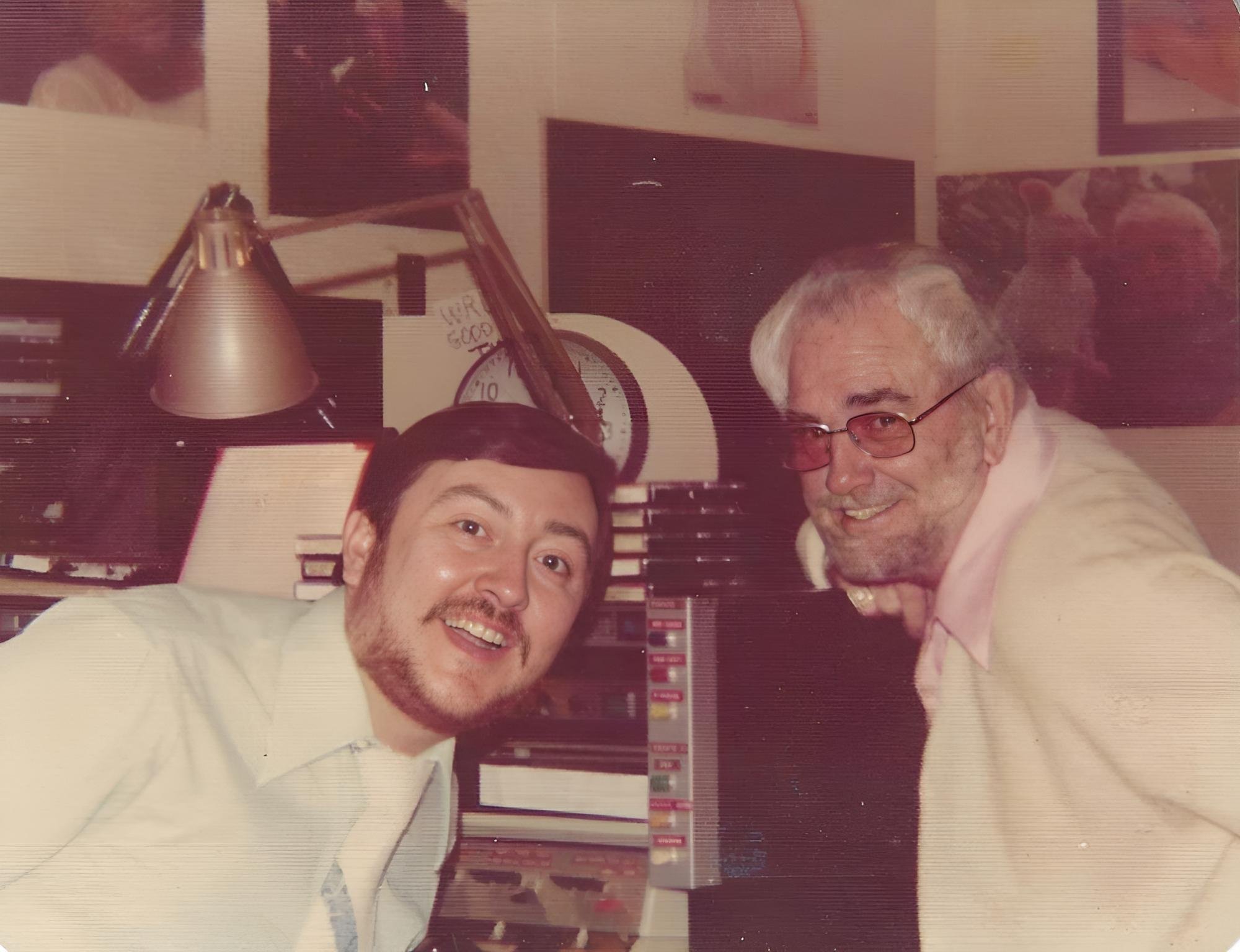

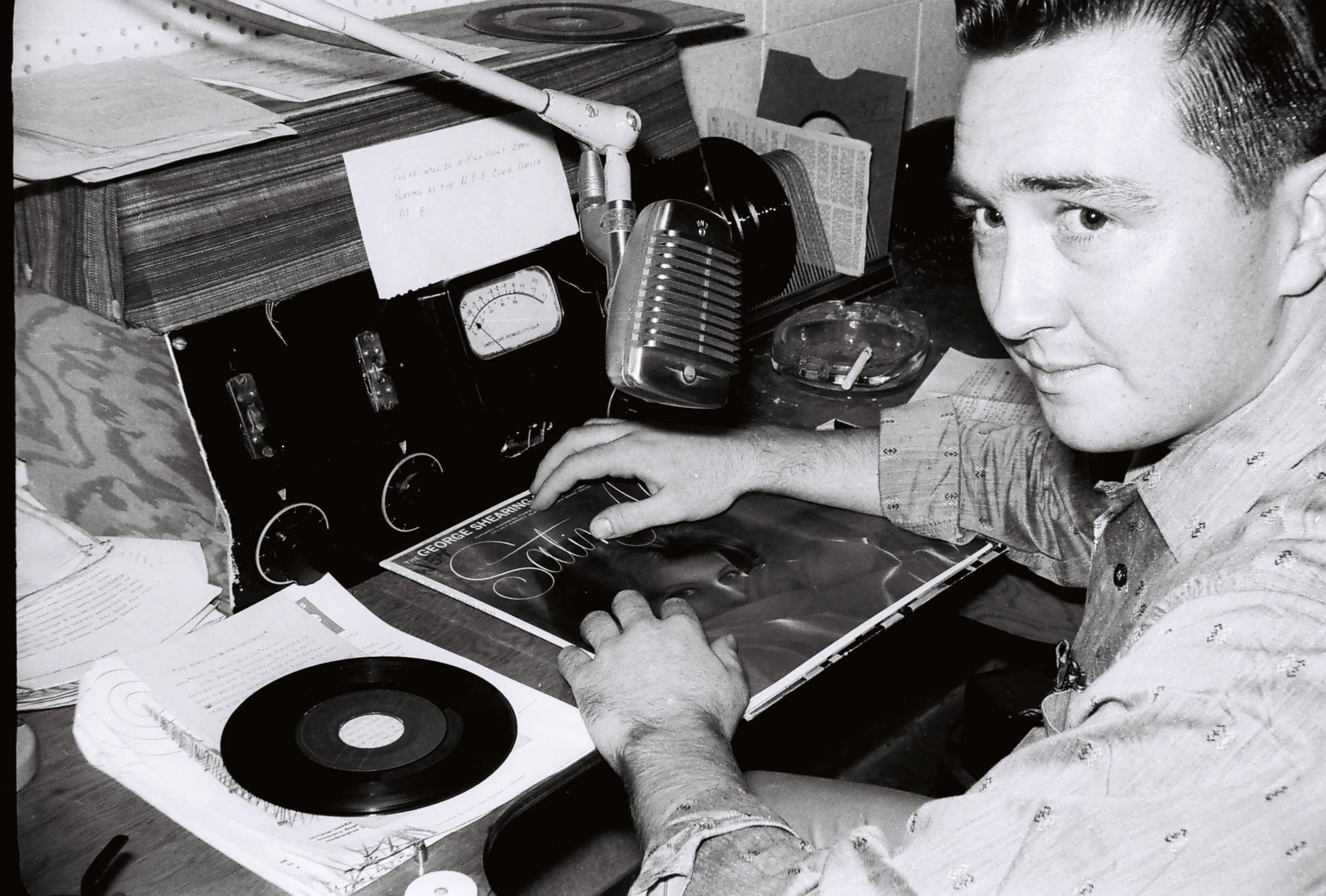

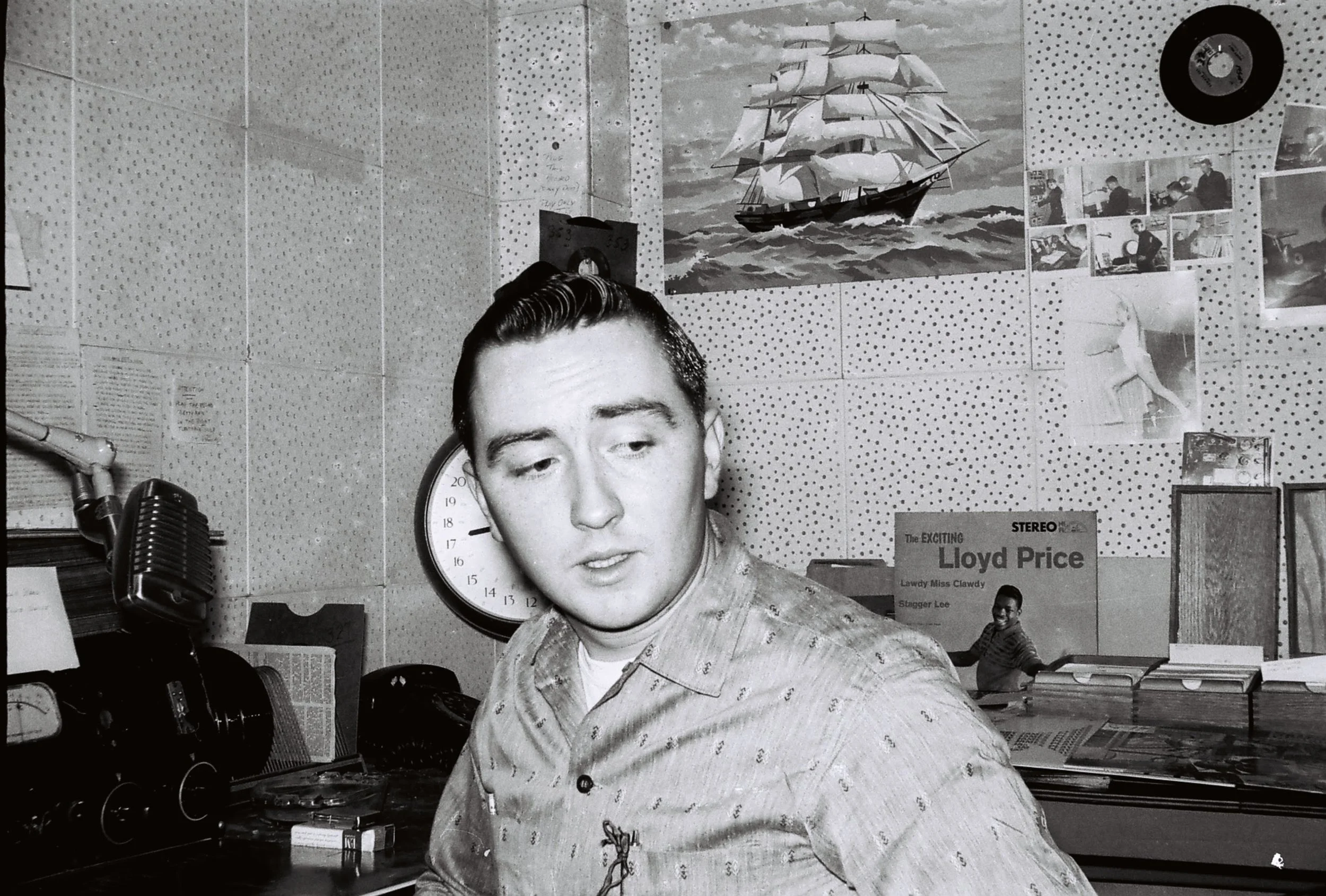

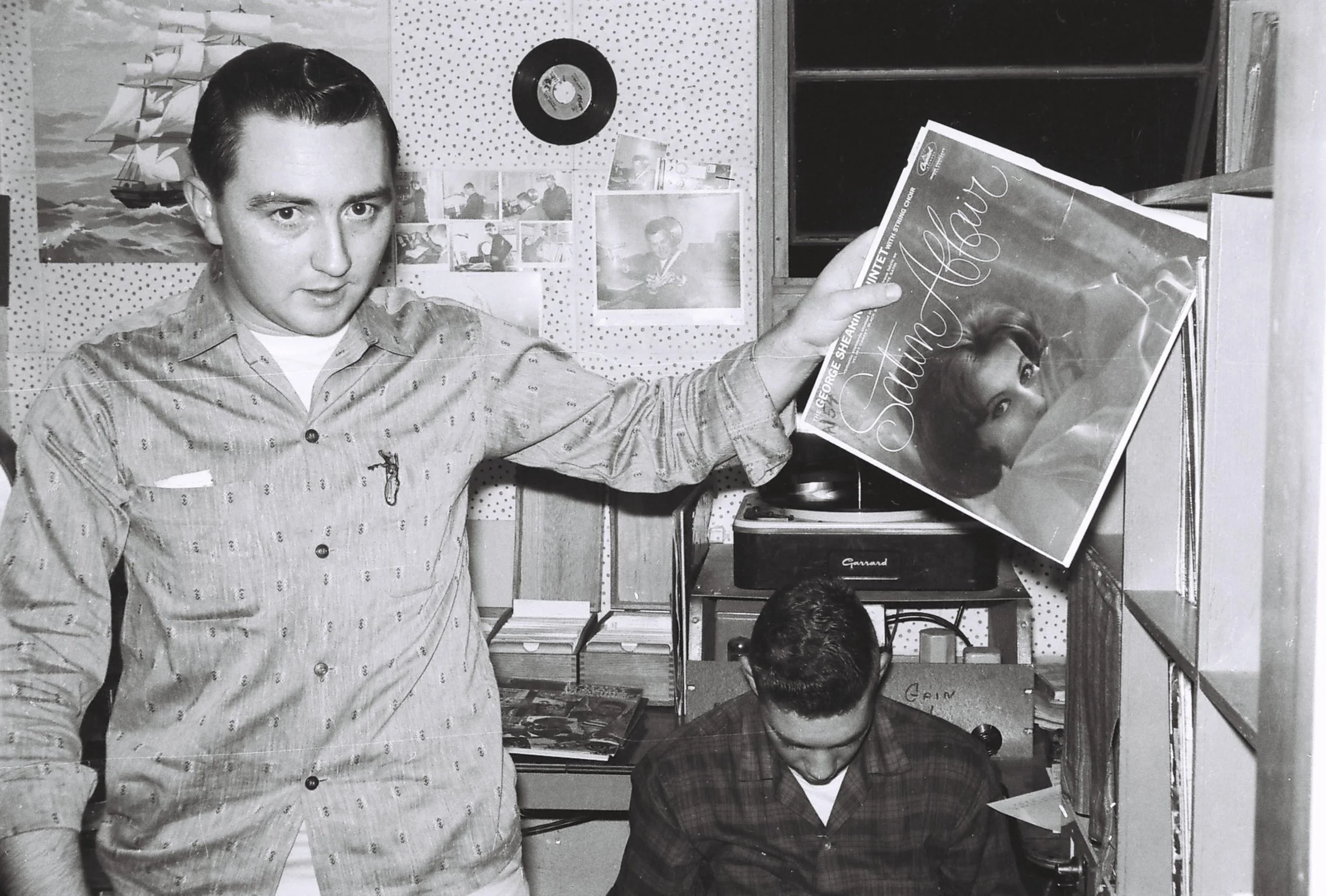

While the secure mission rooms focused on intelligence, the base also hosted a radio station. JC became its program director, and here the sounds were entirely different. Instead of static and intercepted chatter, it was the upbeat crack of a needle on vinyl, baseball scores read between songs, and a familiar voice carrying across the airwaves. To the airmen, it was a reminder of home. To the local Turkish community, it was a bridge of goodwill. And to outsiders, it was a plausible cover, masking why so many operators with headsets were always listening.

At Karamürsel, JC lived a dual role. He was an intelligence specialist, straining to hear Soviet bombers and fleets over the background hiss of radios. He was also a broadcaster, spinning music that lifted spirits and built trust with the host community. His service in Turkey reflects the hidden nature of the Cold War, where sound itself was both weapon and comfort, and where a young airman from Pawtucket was already developing the voice that would later become a fixture in American broadcasting.

Early 1960s: JC serves at TUSLOG Det-3 in Turkey as part of his Air Force service.

During the most dangerous years of the Cold War, Karamürsel Air Station in Turkey was one of America’s most important listening posts. TUSLOG Detachment 3 provided a constant stream of signals intelligence that shaped U.S. and NATO responses to Soviet activity.

JC arrived in Turkey on May 19, 1960, only weeks after a U-2 reconnaissance plane flown by Francis Gary Powers had been shot down over the Soviet Union. The timing made clear how tense the environment had become. Positioned on the Sea of Marmara with direct access to the Black Sea, TUSLOG Detachment 3 tracked Soviet bomber patrols, naval movements, and radar activity. The reports gathered there were sent up the chain within hours, reaching military and political leaders in Washington and Brussels.

In 1961, while JC was still stationed in Turkey, attention shifted to Cuba. President John F. Kennedy’s administration attempted to oust Fidel Castro with the Bay of Pigs invasion in April, which failed within days. Later that year Kennedy approved Operation Mongoose, a campaign of covert pressure against the Castro regime. Though JC returned to the United States on November 29, 1961, to continue duty at Goodfellow Air Force Base in Texas, the unit he had served with remained critical to intelligence collection.

That role was proven beyond doubt during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. Photographs confirmed the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba, but intercepted communications were needed to gauge readiness and intent. TUSLOG Detachment 3’s work helped clarify the scope of the Soviet buildup, giving Kennedy the confidence to enforce a naval blockade and negotiate from a position of strength. The crisis ended with an agreement to remove the missiles from Cuba, paired with a quiet U.S. decision to withdraw its own Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

The resolution of the crisis highlighted the value of signals intelligence in preventing nuclear conflict. The operators at Karamürsel, like JC during his tour, carried out work that remained unseen by the public but was essential to national security. He often reflected on the contrast between the long hours in the intercept room, headphones pressed tight against the static of Soviet pilots and warships, and the lighter moments spent behind the microphone at the base radio station. Both roles demanded focus, but one offered a reminder of home, music, and connection in the middle of an uncertain world. Although JC had returned stateside before the Cuban standoff, the skills and perspective he gained in Turkey stayed with him for life and shaped the career in broadcasting that would follow.

1961-1963: JC returns to the United States and continues his broadcasting career in the Air Force in San Angelo.

After completing his tour at Karamürsel Air Station in Turkey, JC returned to the United States and was assigned to Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas. Many of the men he had served with overseas arrived there as well, and together they brought back the discipline and skills they had developed during the Cold War.

Goodfellow was in transition. It had recently moved from Air Training Command to the United States Air Force Security Service, and its mission now focused on advanced cryptology and intelligence instruction. JC stepped directly into that world. He carried a top clearance and spent long hours decrypting Russian communications, including ship to shore traffic from naval units, coded orders between radar and missile sites, and routine messages from Soviet air operations. Reports built from this work did not remain in Texas. They were passed to the National Security Agency and Strategic Air Command, where they were combined with other intercepts to shape America’s defense posture during a period of nuclear tension.

The secrecy of that work defined his days, but it was balanced by something very different at night. JC poured his energy into the base radio station, where from late 1961 until his discharge in July 1963 he served as program director. His humor and quick wit made him the right fit to lead an eighty man rotation of announcers and technicians. He trained new voices, set the schedule, and gave the station a sound that reflected both discipline and personality.

Music was central. JC had a deep knowledge of records and a natural sense for what people wanted to hear. He spun Elvis Presley’s “Return to Sender,” Ray Charles’ “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Patsy Cline’s “Crazy,” and Motown hits like The Miracles’ “You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me.” He mixed those with the Four Seasons’ “Sherry,” Roy Orbison’s “Crying,” and the early surf sound of the Beach Boys. Requests arrived from the barracks and offices, and he made a point to read birthday greetings, baseball scores, and small personal notes on air. Listeners tuned in not only for the music but also for his voice, which carried through dormitories, mess halls, classrooms, and offices.

The contrast between his roles was sharp. By day he sat in secure rooms with headphones on, listening for faint Soviet signals that demanded exact translation. By night he leaned into a microphone, playing songs that reminded men of home and lifting morale in a remote part of Texas. Both required precision and focus, but one fed directly into national security while the other held together a community of airmen.

For JC, Goodfellow was more than another posting. It was the place where his technical discipline and his personality as a broadcaster came together. Intelligence work gave him structure and purpose. Radio gave him presence, timing, and connection. Those years were a proving ground that prepared him for the broadcasting career that would define his life after the Air Force.

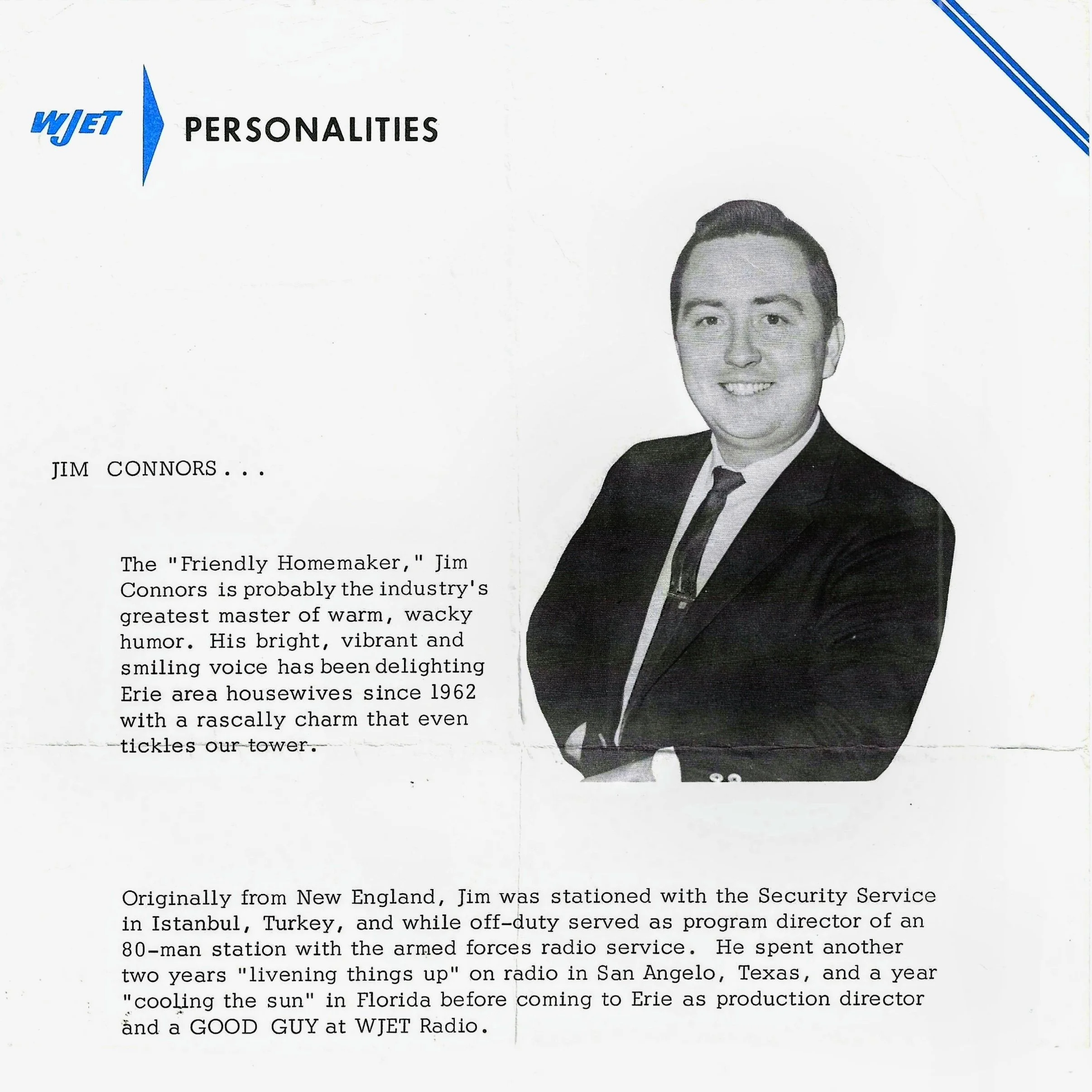

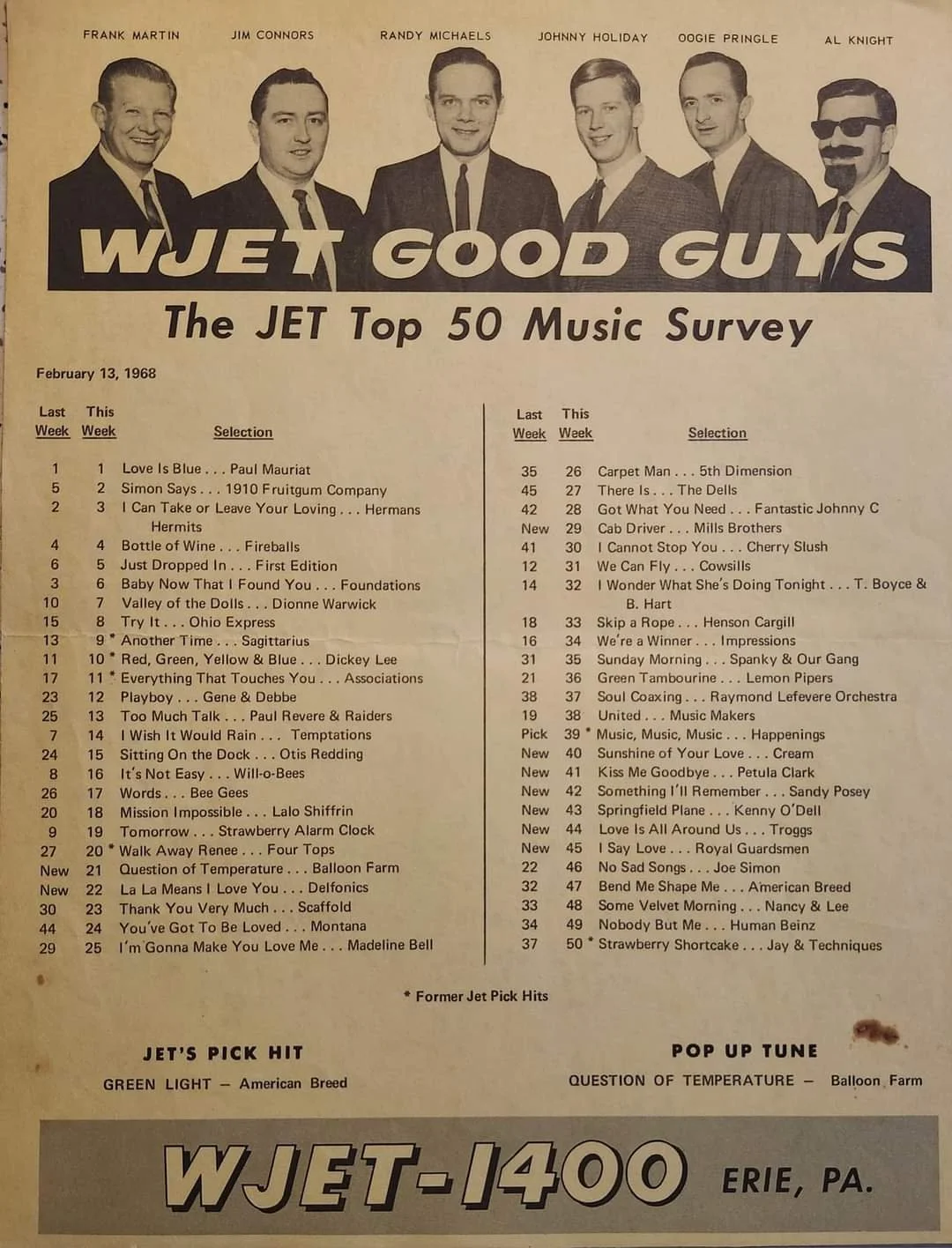

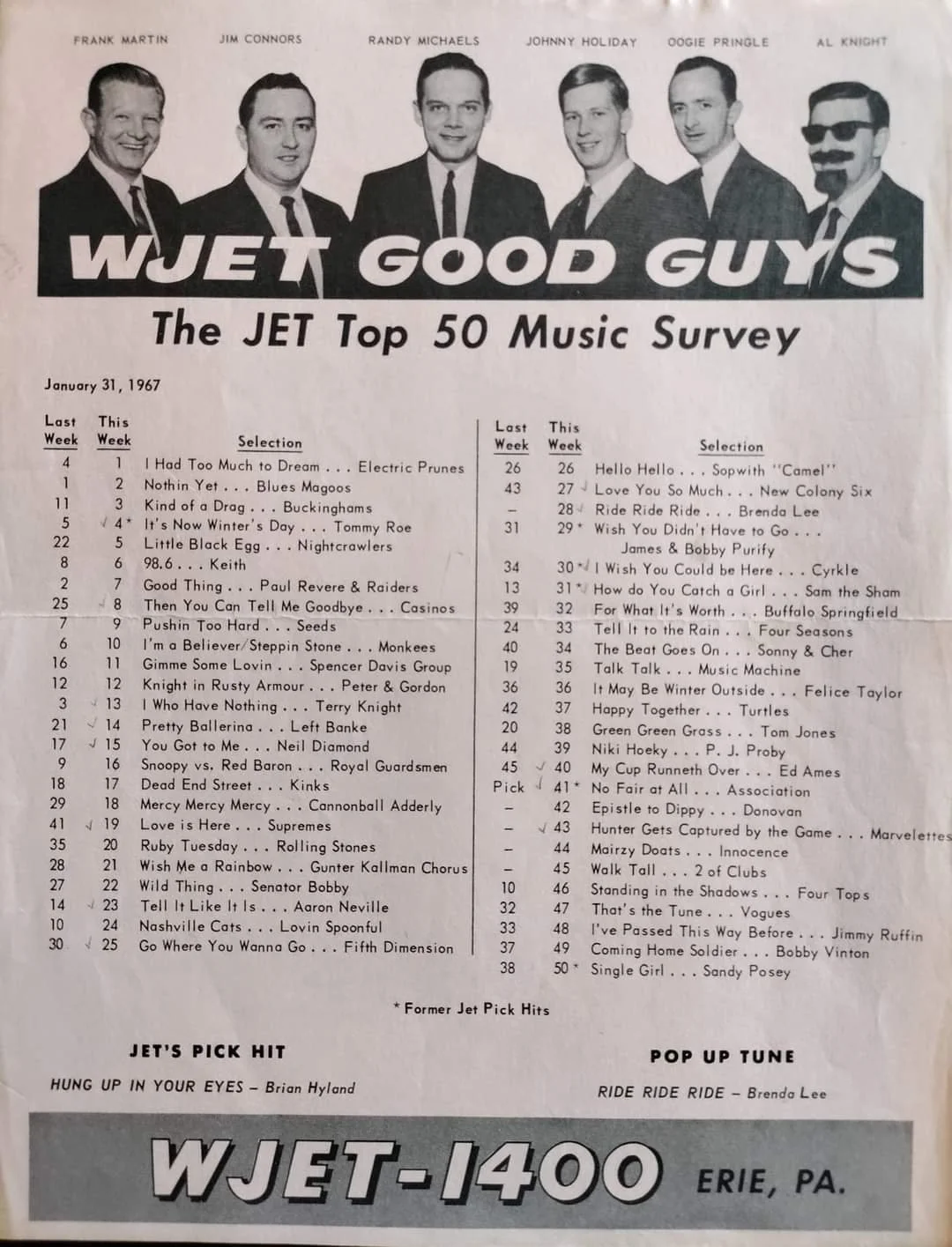

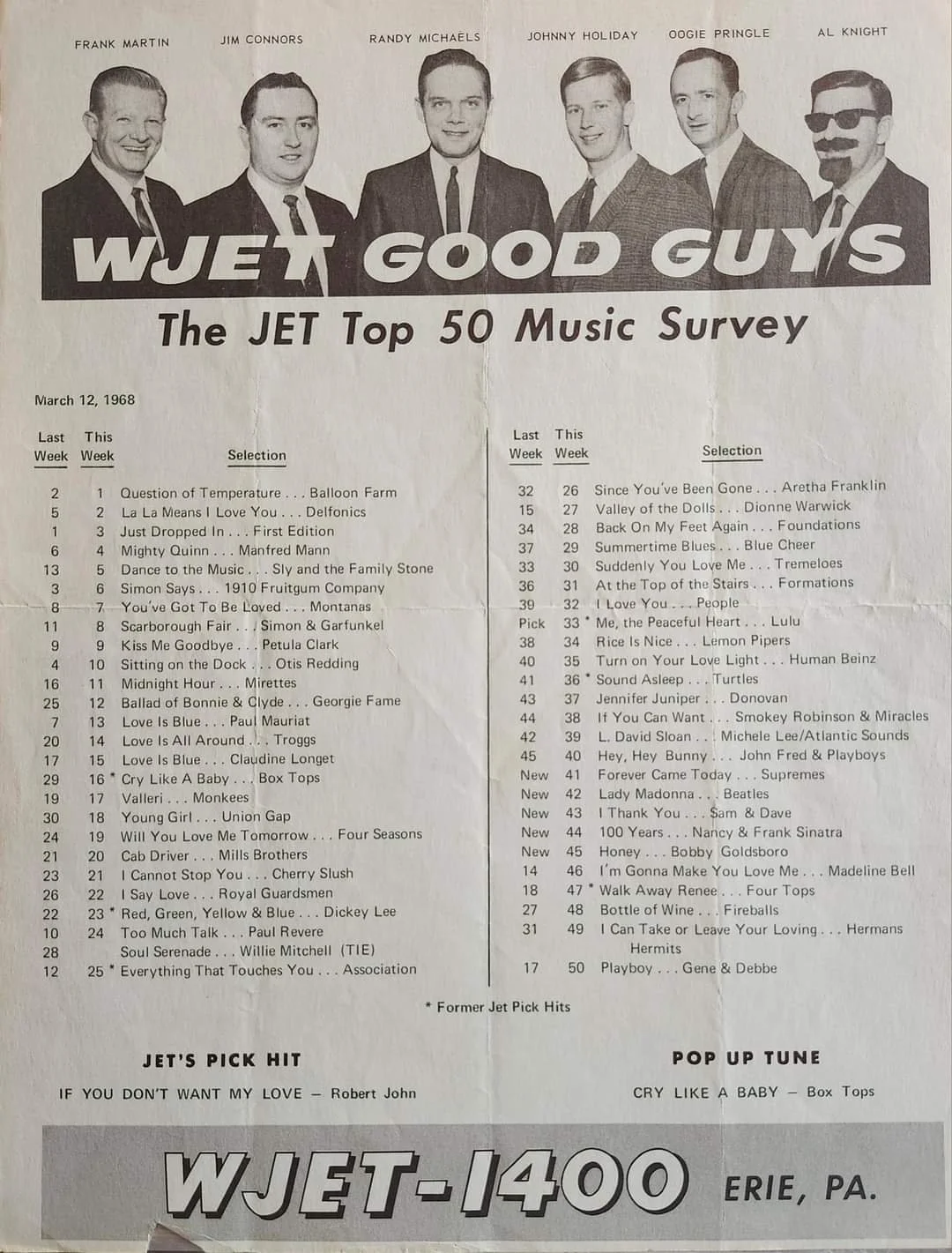

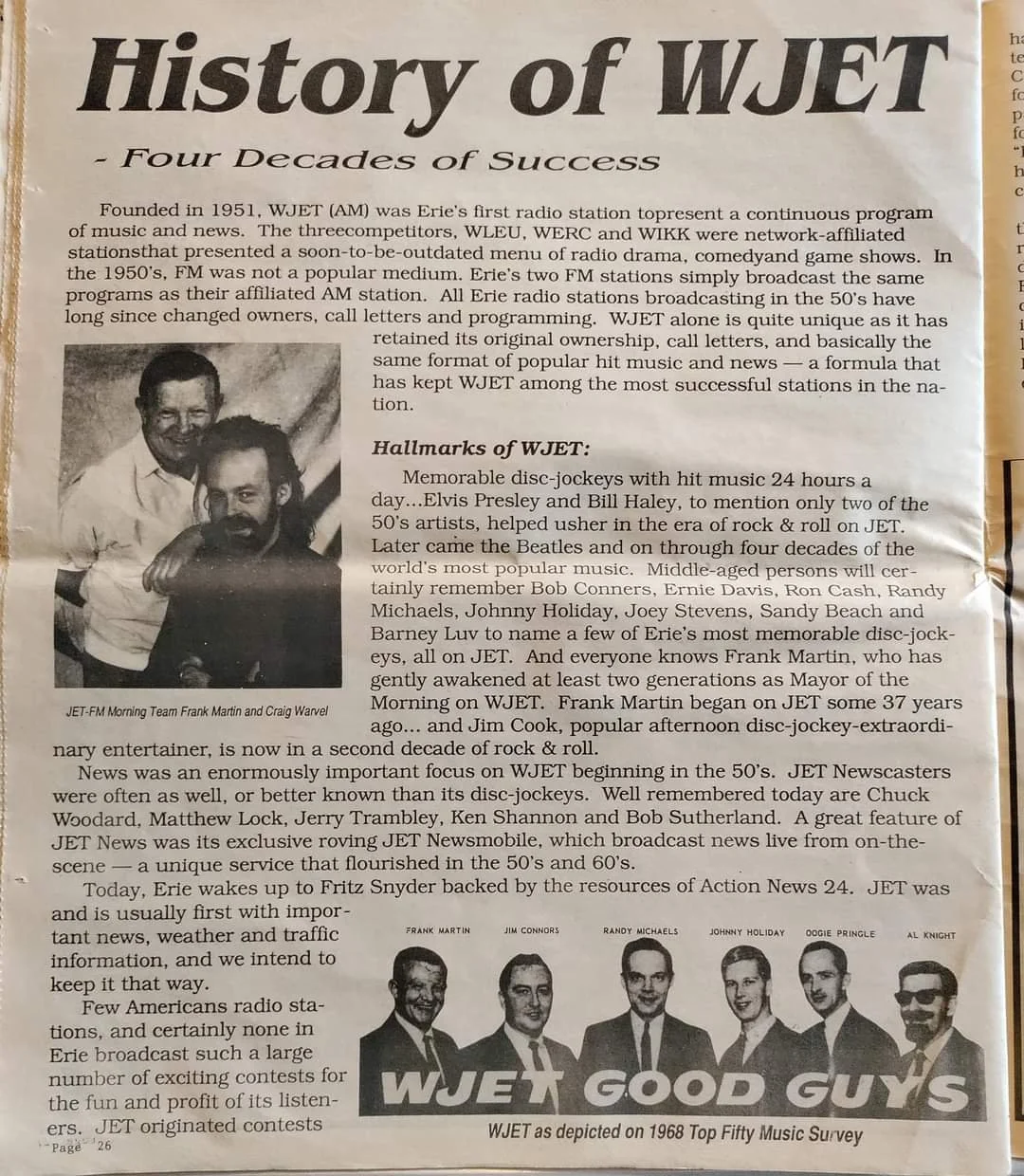

WJET

JC's Civilian Radio Debut:

WJET in Erie, PA

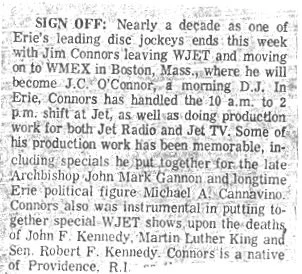

1965: JC begins his civilian broadcasting career, joining WJET in Erie, Pennsylvania.

After completing his service with the United States Air Force Security Service on July 5, 1963, Jim Connors, known as JC, stepped away from the world of secrecy and discipline he had lived in for years. He later described that next chapter as “a year of cooling off in the hot sun of Florida.” The phrase was his own, and it carried weight. It was his way of decompressing from intelligence work and base broadcasting before stepping into the career that would define him.

When JC was ready, he turned to Erie, Pennsylvania, and WJET. At that time, WJET was still young but already gaining momentum. Founded by Myron Jones, who had personally built and wired the studios, the station had gone on air in 1957 as a 250 watt daytimer on 1570 AM before moving to 1400 AM. Even with modest power, WJET quickly became Erie’s most talked about station, driven by youthful energy and a hunger to do more than the competition.

Myron saw in JC exactly what he needed to push the station forward. It was not just a voice he was hiring, but a complete package. JC had personality that jumped off the microphone, discipline from his Air Force service, and the ability to connect with people on and off the air. He could write copy, create engaging features, and represent the station in the community with confidence. For Myron, who was still in his twenties and ambitious about making WJET the top station in Erie, JC was the kind of talent who could help make that happen.

JC started with the lunchtime show, and his style clicked immediately. He had a way of speaking that made listeners feel like he was talking directly to them, and his humor and warmth kept them tuned in. His ratings soon passed even the morning crew, a rare accomplishment in radio. Under his influence, WJET became more than a jukebox playing hits. It became the voice of Erie.

The “Good Guys” team brand gave the station personality, but JC gave it weight. He mixed rock and roll with rhythm and blues, jazz, country, and the emerging sound of Motown. By late 1963 and into 1964, as the British Invasion began, WJET was one of the first stations in the region to bring that new sound to listeners. JC was at the front of it, introducing Erie audiences to records that would become anthems of a generation.

Competition in Erie was strong but uneven. Long established stations like WLEU and WWGO had larger signals and older audiences, but they could not match WJET’s pace or style. Their programming leaned conservative, while WJET was modern, quick, and tightly connected to its listeners. Even with less power, WJET consistently topped the ratings. Its DJs, JC among them, were household names. Advertisers wanted time on WJET because they knew their messages would be heard, and young people tuned in daily to know what was happening in music and in their city.

The station’s rise was tied closely to Erie itself. The city in the early 1960s was alive with industry. Steel plants and factories lined the lakefront, while neighborhoods of working families stretched toward Presque Isle Bay. Radios in homes, shops, and cars carried WJET throughout the day. On summer nights, its sound floated out of parked cars along the waterfront or through open windows in city neighborhoods. JC’s voice became part of that daily rhythm, connecting the music of the moment to the pulse of the community.

Young listeners were especially drawn to him. JC hosted record hops in school gyms and church halls, bringing the same energy he carried on air into packed rooms where teenagers danced to the songs he introduced. He was visible at charity events and local promotions, shaking hands, giving shout outs, and building relationships that made him more than a voice on the radio. For a generation coming of age in Erie, JC was both entertainer and guide, the man who brought the newest sounds into their lives and connected them to the broader culture that was changing the country.

For JC, WJET was more than just his next job. It was the place where his military discipline, his Florida reset, and his natural personality as a broadcaster came together. For Myron, hiring JC was more than filling a slot. It was placing his station in the hands of a figure who embodied what he wanted WJET to be: energetic, connected, and unforgettable.

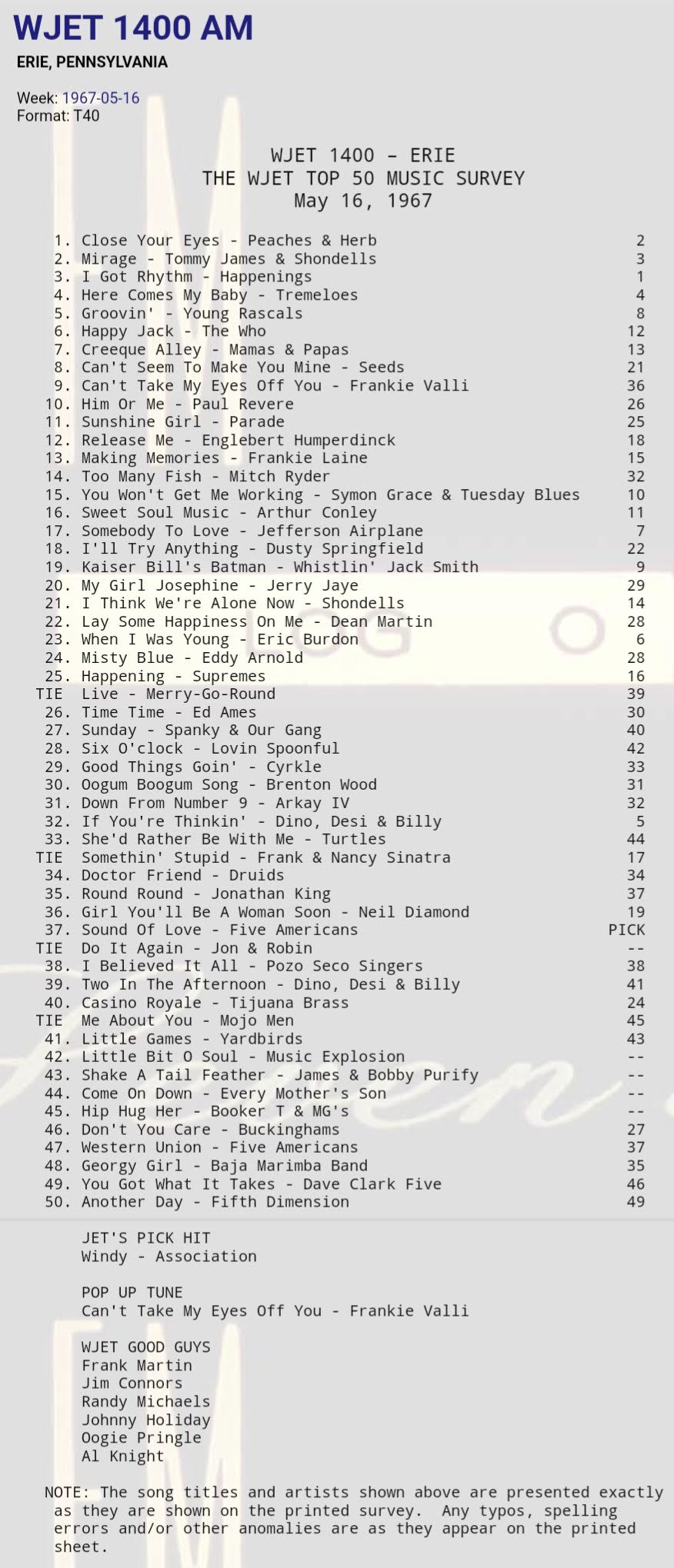

1967: Tommy James and the Shondells achieve a gold record under JC's tenure at WJET.

By 1967, Jim Connors, known as JC, had become one of the most recognizable voices on WJET. That year he played a decisive role in elevating the career of Tommy James and the Shondells. WJET was more than a station that played records. Under JC’s leadership, it was a tastemaker, and the way he promoted their music showed how powerful a local broadcaster could be in shaping national success.

The story began a few years earlier with a forgotten single called “Hanky Panky.” Originally recorded in 1964, the track sat unnoticed until a bootleg copy surfaced in Pittsburgh in 1965. Local DJs began playing it, and the response was explosive across western Pennsylvania. By the time it reached Erie, WJET and JC gave it constant rotation, pushing the sound across the city, into northeastern Ohio, throughout Pennsylvania, and into southern Ontario. That wave of airplay turned a discarded single into a regional sensation. It was this surge of attention that caught the interest of Roulette Records, which signed Tommy James and the Shondells and set them on a path to national recognition.

Roulette Records was run by Morris Levy, a powerful figure in the New York music industry. Levy was known for his forceful and sometimes controversial business style. The label had a reputation for leaning on broadcasters to give its artists exposure, often through pressure and persistence. Yet in the case of Tommy James and the Shondells, the breakthrough in Erie did not come from industry pressure. It came from JC’s conviction that the music was worth playing. He gave the band credibility with audiences because his support was genuine.

Tommy James later acknowledged that it was the DJs of Pennsylvania and Ohio who made the difference. Without their early airplay and enthusiasm, “Hanky Panky” would have remained a forgotten track. JC was one of those central figures, and his role in bringing the band from local curiosity to national hitmaker cannot be overstated.

By 1967, JC’s involvement with the band was at its peak. He did not simply add their songs to the playlist. He pushed them forward with frequent rotation, energetic introductions, and his trademark confidence on the air. Songs like “I Think We’re Alone Now” and “Mony Mony” became fixtures of his shows. With his backing, they leapt from regional popularity into national chart success.

At that time, gold records were not yet governed by the standardized system of the Recording Industry Association of America. Instead, they were produced and presented by record companies themselves, usually to acknowledge sales milestones of half a million singles or one million albums. When JC was awarded a gold record for his role in breaking Tommy James and the Shondells, it came directly from the industry as a mark of gratitude. It recognized that his influence in Erie and the surrounding region had helped push the band’s records to national prominence.

For JC, the gold record was more than a piece of hardware. It validated the qualities he had carried from his Air Force years: discipline, a strong sense of responsibility, and the authority of a man whose word mattered. Just as his work in intelligence had required precision and reliability, his work behind the microphone demanded trust and judgment. Listeners believed him, artists valued his support, and record labels recognized his impact. For WJET and for Erie, the honor showed that the voice of a single broadcaster could ripple outward and shape the sound of an era.

1969: WJET and JC Bring Blodwyn Pig’s Ahead Rings Out to American Audiences.

In 1969, while at WJET, Jim Connors, known as JC, helped bring attention to Blodwyn Pig’s debut album Ahead Rings Out. His steady promotion on air and his advocacy within the local music scene introduced listeners to a record that sounded different from anything else that year. Blodwyn Pig, formed by guitarist Mick Abrahams after leaving Jethro Tull, blended jazz, blues, and rock. The addition of saxophone and flute gave the band a sound that set it apart.

The album included songs such as “Dear Jill” and “See My Way,” which showed both musical range and lyrical depth. The writing touched on personal themes that connected with audiences during a period of change and cultural unrest. The late nineteen sixties was a time when listeners were open to new ideas and sounds, and Blodwyn Pig met that moment.

JC’s support helped the album gain traction in the United States. He gave it regular airplay, spoke directly to his audience about its importance, and treated it as music worth seeking out. His instincts had already helped push pop acts like Tommy James and the Shondells into the spotlight. With Blodwyn Pig, he showed that he could also recognize the strength of a more experimental sound.

The record proved his judgment correct. Ahead Rings Out reached number nine on the United Kingdom Albums Chart and entered the United States Billboard 200, where it peaked at number seventy-seven. In Britain the album sold more than one hundred thousand copies, a significant achievement in that market at the time. Since the British Phonographic Industry had not yet created a formal certification system, Island and Chrysalis produced gold discs themselves to mark the milestone. The award presented for Ahead Rings Out is regarded by collectors and historians as an authentic acknowledgment of commercial success. JC was awarded a gold record for his role in bringing Ahead Rings Out to American audiences. The presentation recognized not only his success in the United States but also how highly his instincts were valued by Island and Chrysalis in Britain, making his influence clear on both sides of the Atlantic.

By the end of the decade, these awards were beginning to form a collection that reflected the arc of his career. Each gold record was more than a plaque on the wall. It was evidence that a broadcaster from Erie had the reach to shape what people were listening to across states and even across the ocean. Labels and artists alike understood that JC was not only a trusted voice with his listeners but also a figure whose judgment could help turn records into successes.

A very special Thank You to John Gallagher of Erie, PA for his continued support and sharing of these surveys!

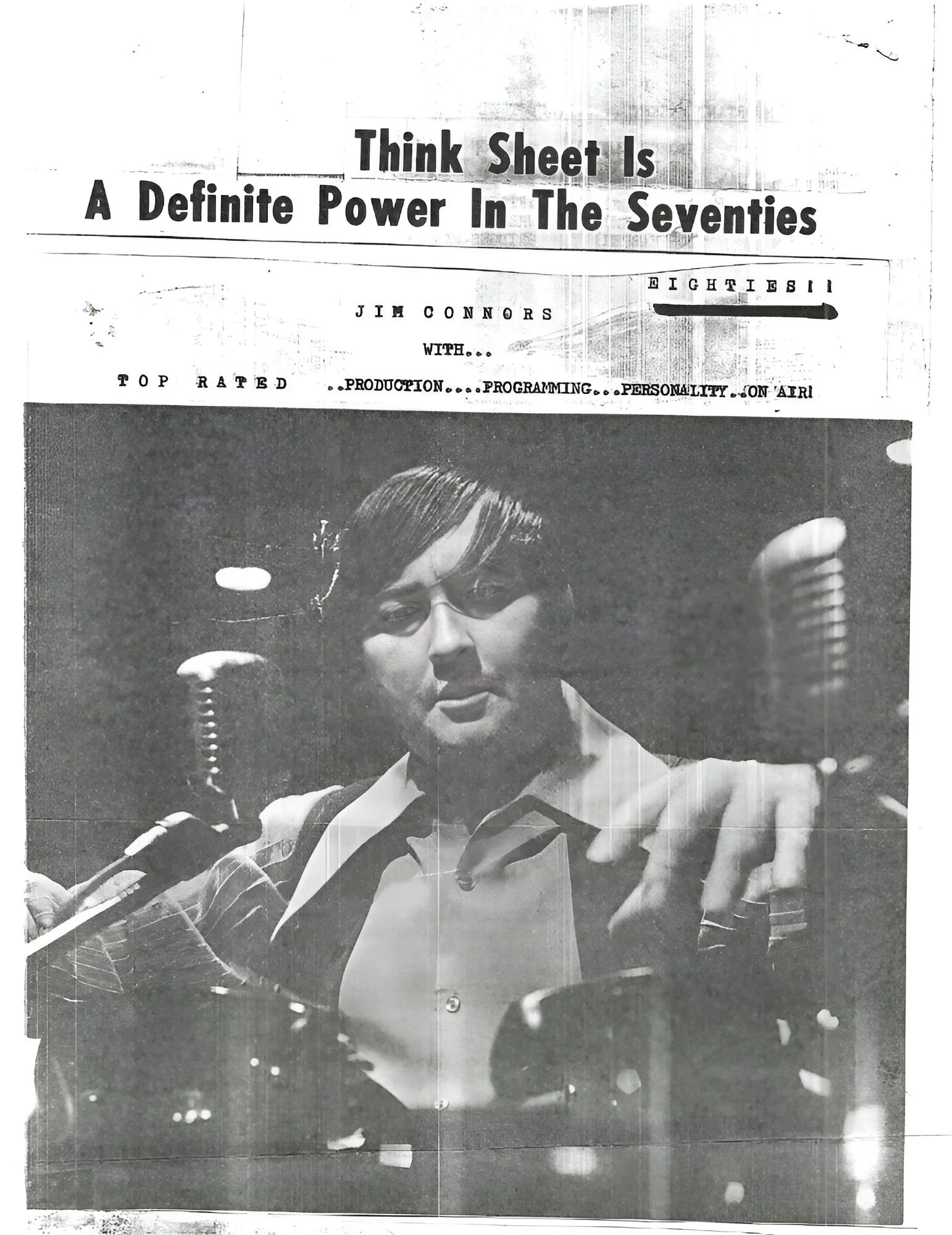

Late 1960s – JC in the Inner Circle of Radio Power Brokers

By the late nineteen sixties, radio was as much about relationships as it was about records. Program directors, label executives, and distributors formed the backbone of the music business. They were the ones who decided what stations played, how records were promoted, and how quickly new releases spread across the country.

At WJET in Erie, JC proved he had the instincts to shape what listeners wanted. But he also understood that success in radio required being connected to the people who made the system run. He built strong ties with program directors at major stations, including John Rook, Bill Price, and Tommy Edwards at WLS in Chicago. Rook was regarded as one of the most influential program directors in America. Price and Edwards were trusted voices who helped guide WLS during its peak years as a national trendsetter. By connecting with men of their stature, JC gained direct insight into programming strategies that kept WJET competitive against stations with far greater resources.

JC also cultivated relationships with the other side of the industry, the executives and distributors who controlled the flow of new music. Vice presidents at labels and regional distributors made sure records reached the right stations, but they relied on program directors like JC to deliver results. He earned their trust by consistently breaking records in Erie that moved sales across the region. When a record spun on WJET under his watch, it often translated into store traffic and chart movement, and the industry noticed.

Networking in this era went beyond socializing. It was a system of constant information exchange, where program directors and executives traded ideas about playlists, promotions, and audience response. JC’s voice was part of that conversation. He wasn’t just a broadcaster in Erie; he was a player in a national network of decision makers whose choices shaped the sound of American radio.

It was this growing reputation, built on both his instincts and his connections, that set the stage for his next move. By the end of the decade, the industry knew JC was ready for a larger stage, and the opportunity would soon come from Boston.

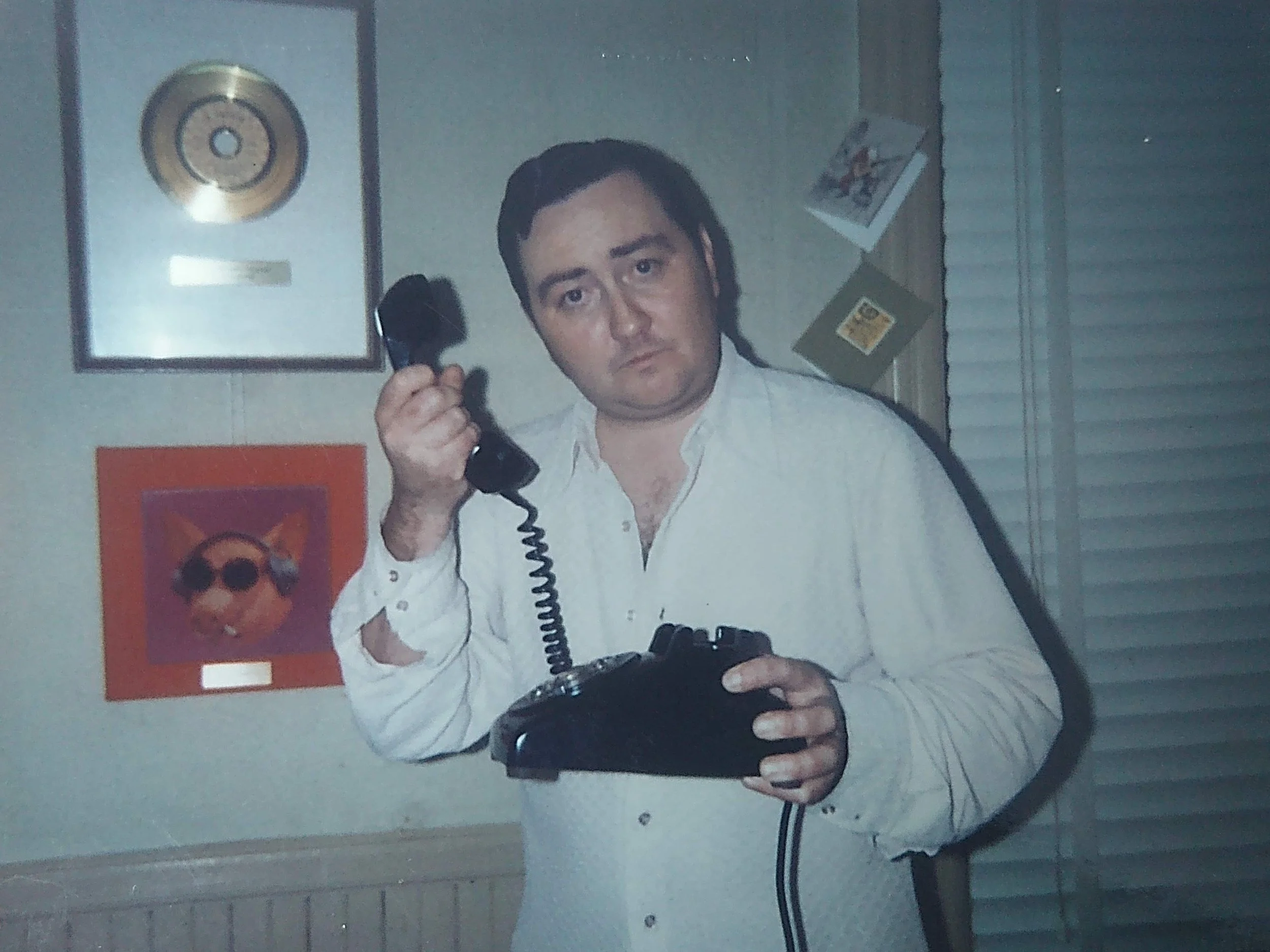

WMEX - BOSTON - 1971

From WJET to WMEX: JC's Major League Call-Up

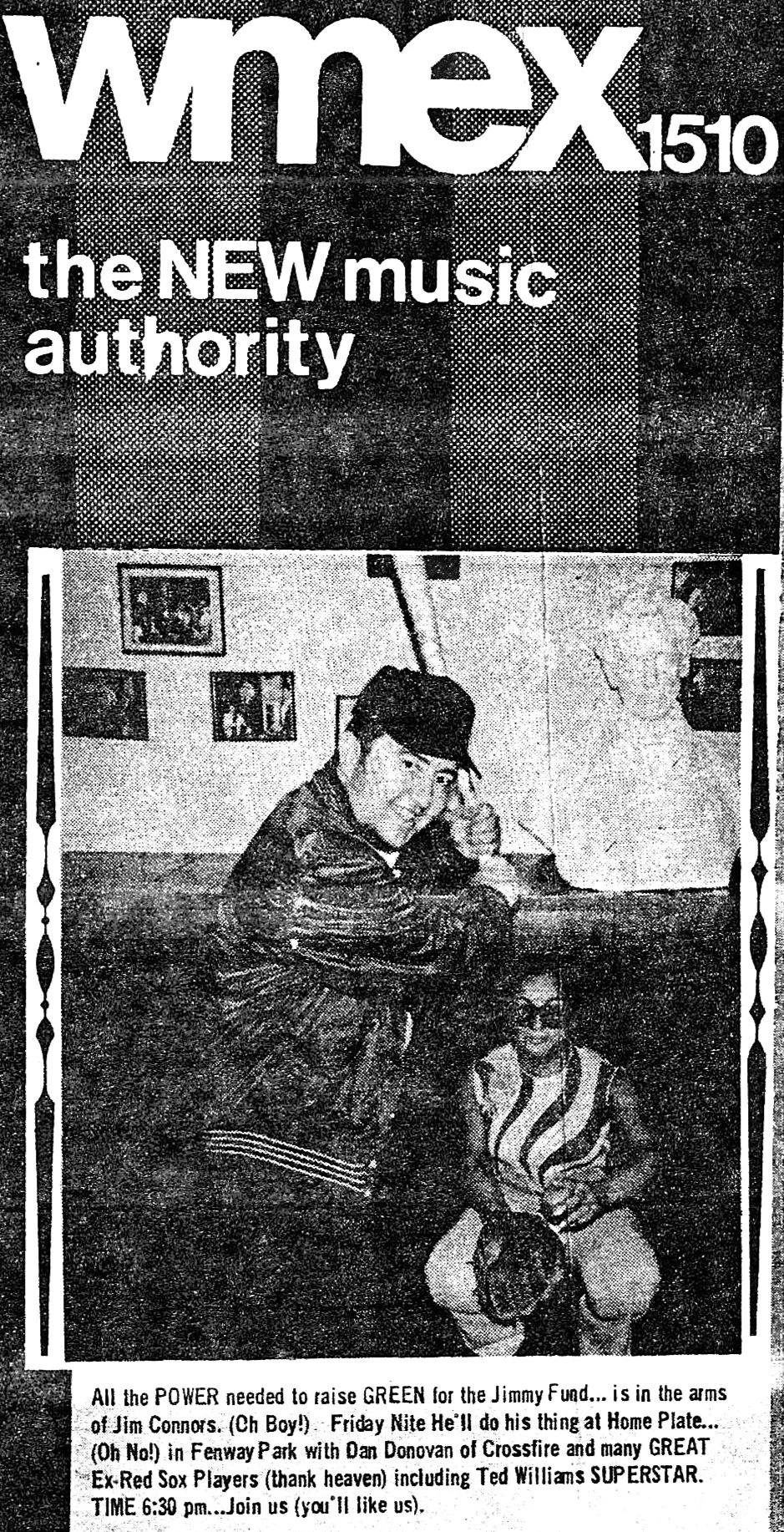

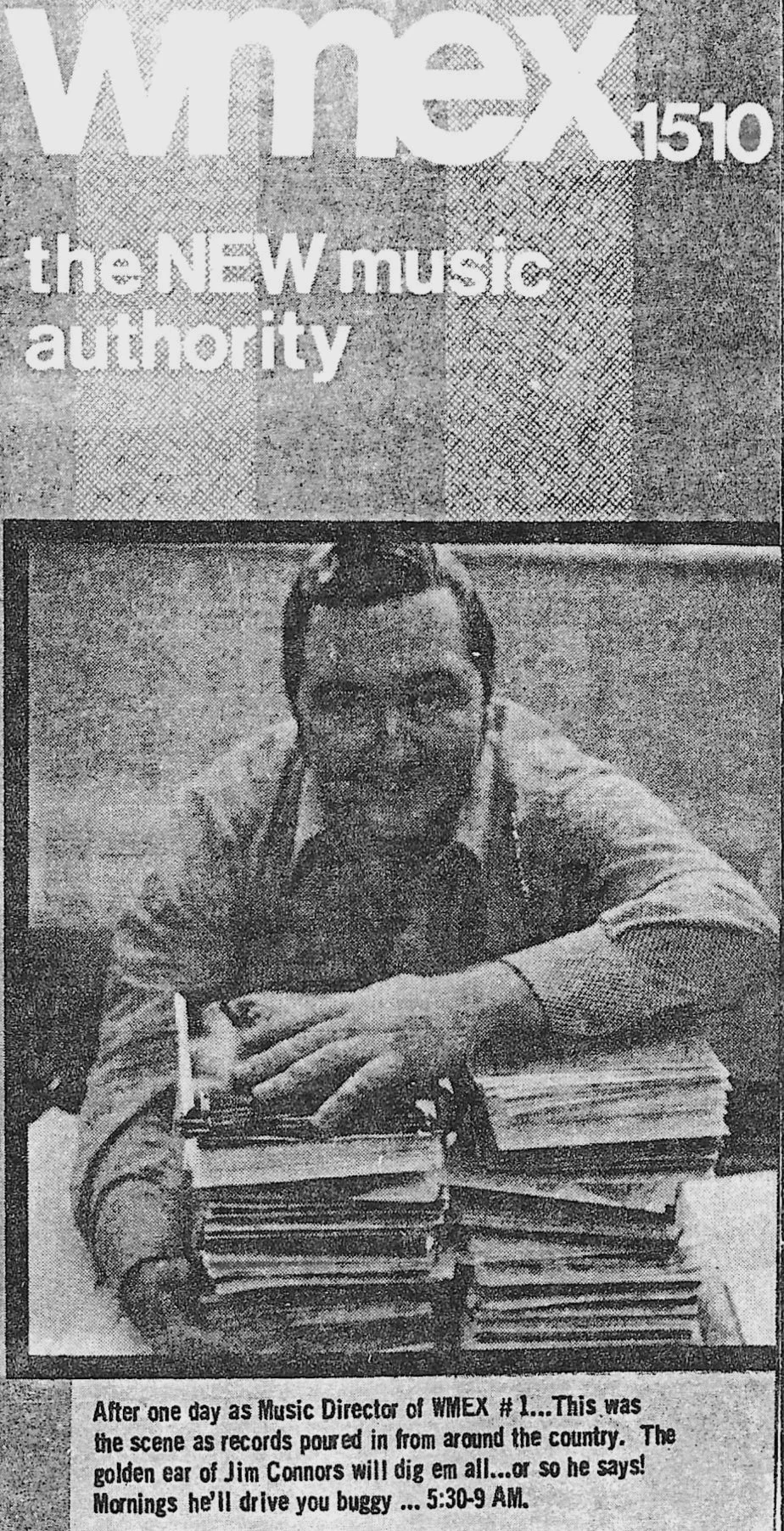

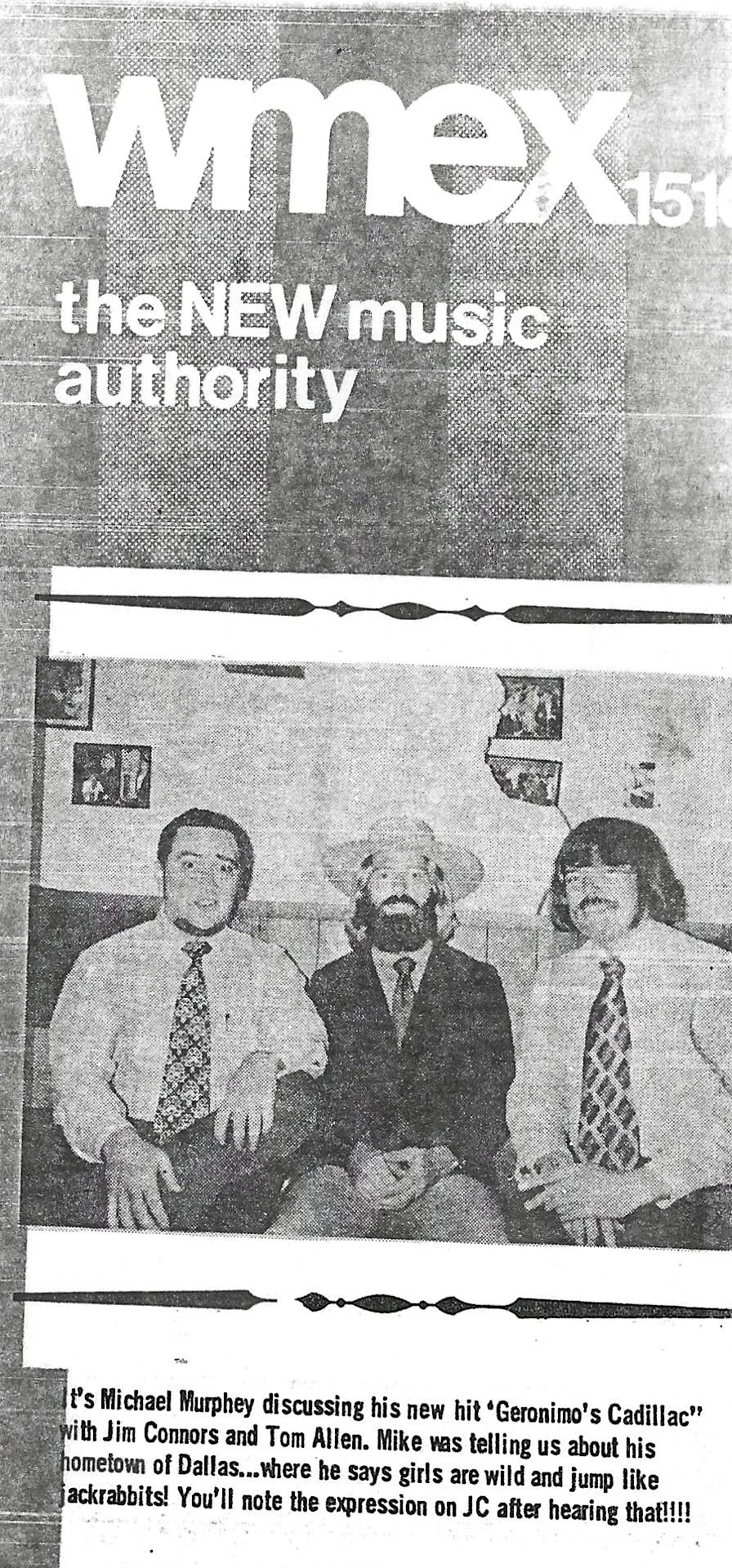

1971 – JC at WMEX: Program Director and Morning Drive in Boston’s Power Market

In 1971, Jim Connors, known to his listeners as JC, entered one of the most competitive arenas in American broadcasting when he joined WMEX in Boston as Program Director and morning drive host. This was more than just a career move. For JC, it was a return to familiar ground. Born and raised in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, he knew the culture of New England and carried with him the pride of a lifelong Red Sox fan. Boston was in many ways a second home, and when he spoke on the air, the connection with the people was immediate and real.

Boston ranked among the top ten radio markets in the country, rivaling New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles in its influence. Its energy came from a rare mix: millions of residents, a student population of more than 200,000, an immigrant backbone built by Irish, Italian, and French Canadian families, and a working-class toughness that shaped its neighborhoods. WMEX had been Boston’s original Top 40 station since 1957, and by the early seventies it remained a commanding voice despite fierce competition from WRKO and WBZ. It marketed itself as the “New Music Authority,” a bold statement that carried weight in a city where music and loyalty mattered.

JC embraced this challenge. As Program Director, he guided the station’s direction, worked with record companies, and kept WMEX competitive in a cutthroat market. As the host of the morning drive slot, from six until ten, he became the trusted voice that greeted Boston every day. Commuters on Route 128, students in Cambridge and Allston, families in Dorchester, and workers in South Boston and Charlestown all tuned in. He gave them music, news, and traffic with a delivery that was both authoritative and familiar, the voice of someone who understood their lives.

The bond was personal. JC’s Irish heritage and Pawtucket upbringing gave him common ground with Boston’s Irish neighborhoods, which were at the heart of the city’s character. He could talk sports with the best of them, especially baseball, sharing in the heartbreaks and hopes of Red Sox fans during the early seventies. In Boston, sports and music were more than entertainment. They were part of identity and pride, and JC’s voice carried both with authenticity.

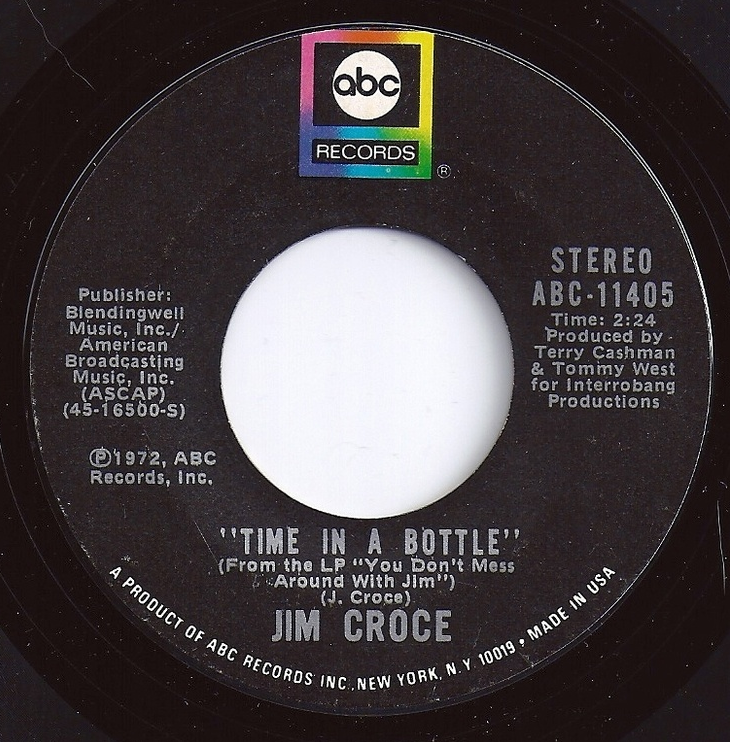

Under his leadership, WMEX helped drive songs that became part of Boston’s soundtrack. Chuck Berry’s “My Ding a Ling,” Mouth and MacNeal’s “How Do You Do,” Wayne Newton’s “Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast,” Joe Simon’s “Power of Love,” and Clint Holmes’s “Playground in My Mind” gained crucial early momentum. He also spotlighted Harry Chapin’s “Taxi” and “WOLD” and Jim Croce’s “Time in a Bottle.” These were not just records. They became tied to Boston’s cultural memory, connected to moments in homes, cars, and neighborhoods across the city.

JC’s creativity extended beyond the studio. Through his company, JC Productions, he created the cover art for the WMEX 1150 Cruisin’ Collection. The project gave listeners a physical piece of WMEX to hold onto, capturing its identity in both music and design.

By 1972, JC’s reputation had spread nationally. At the National Association of Broadcasters convention, he was seen as a programmer with the instincts to launch records in both midsize and major markets. His growing collection of gold records confirmed what Boston already knew: his choices on the air moved people, moved sales, and helped build careers.

But it was Boston itself that meant the most to him. He loved its toughness, its passion, and its people. He felt at home in the neighborhoods, whether shaking hands at live events, sharing a laugh with students and working families, or trading stories with local business owners. WMEX gave him a powerful platform, but it was the bond with the city and its people that defined those years. JC had come from Pawtucket, carried the heart of a Red Sox fan, and found in Boston a place where he could give his best and be embraced in return.

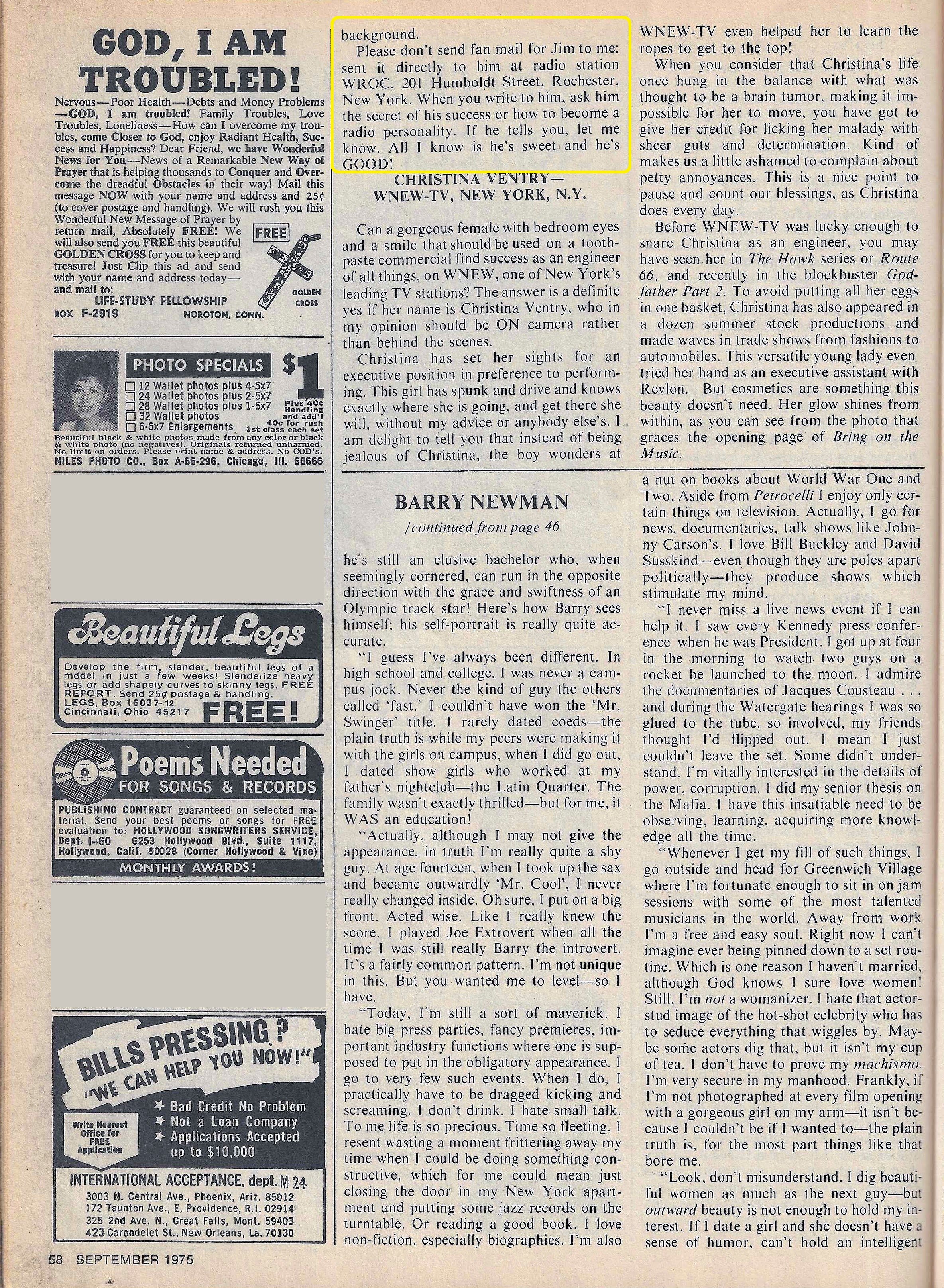

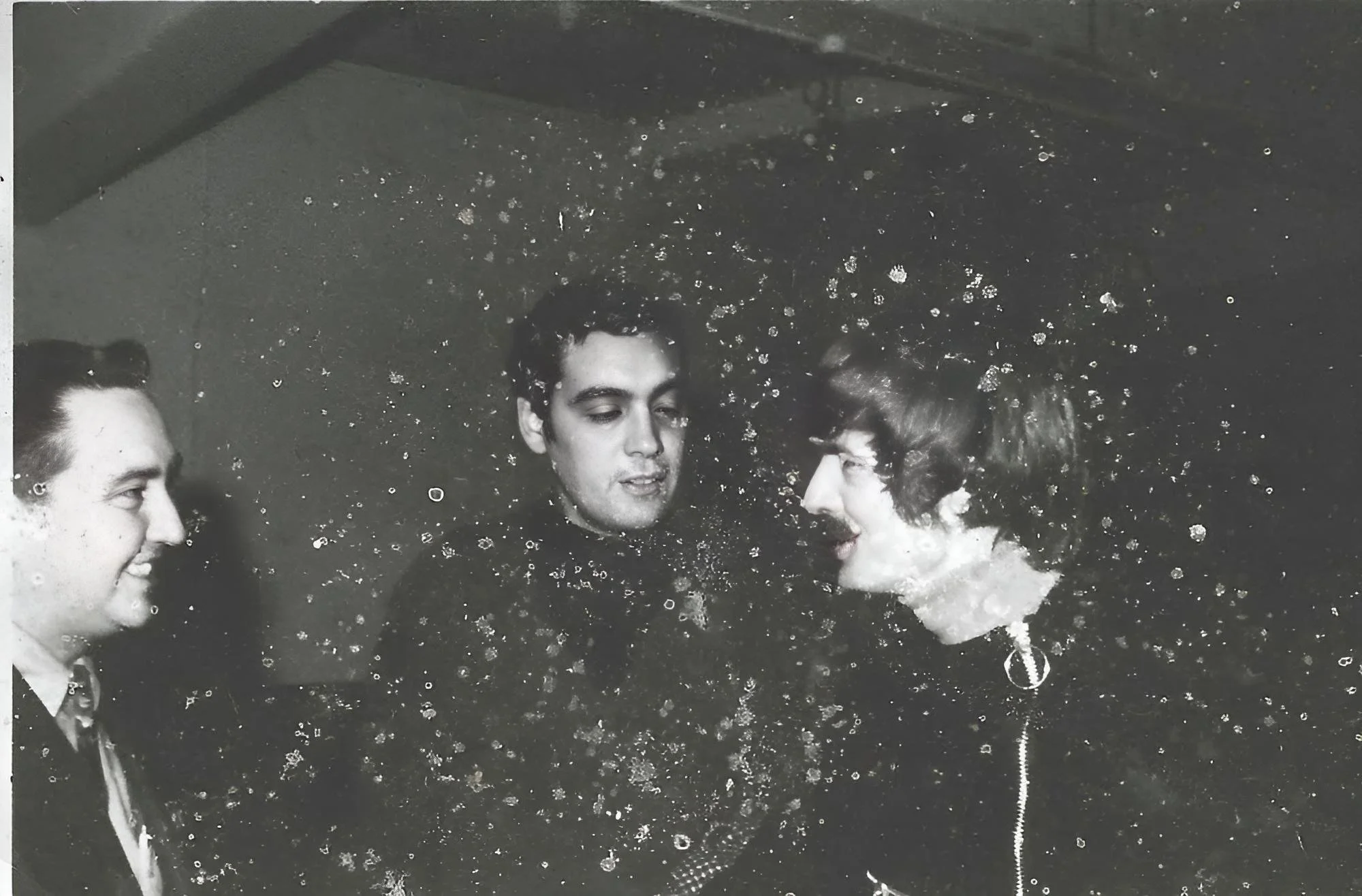

1971 – JC Meets Harry Chapin: A Conversation that Sparked “WOLD”

In 1971, Jim Connors, known as JC, met Harry Chapin in Boston while promoting a concert for WMEX at Symphony Hall. Chapin, still an emerging performer, opened for Carly Simon. WMEX carried weight as Boston’s “New Music Authority,” and JC was there both as the voice of the station and as a trusted figure in the city’s music community. What might have been a brief introduction turned into a long and meaningful exchange. JC and Chapin spoke about the lives they led, about how performers and broadcasters shared a constant demand to give themselves fully to their audiences, and about the sacrifices hidden behind the spotlight.

Chapin was struck by the honesty of their talk. JC spoke from experience as a disc jockey who lived by ratings and long hours, a man who carried the pride of his work but also the personal cost of always being present for his listeners. Chapin, who was beginning to earn recognition as a songwriter and storyteller, understood immediately. Both careers carried a transient quality. Both demanded energy at the expense of privacy. Both often left men older than their audience working in industries built around youth.

Those reflections lingered with Chapin and became the foundation for WOLD, the song he released in 1973 about a radio man whose career and family life bore the marks of years spent serving an audience. The seed of that song began in Boston, in his conversations with JC, where the realities of a broadcaster’s life were made clear.

Their connection grew stronger when Chapin released Taxi in 1972. At more than six minutes, it was an unconventional single, part ballad and part short story, and many program directors hesitated to give it airtime. JC did not. He trusted Boston’s people to embrace it. He knew the city’s neighborhoods, from Dorchester to Southie to Cambridge, would recognize themselves in its honesty. WMEX’s identity as the “New Music Authority” gave him both the freedom and the credibility to put the record in rotation, even when others doubted.

The response in Boston was immediate and overwhelming. Phone lines at WMEX rang with requests, college students passed the word across campuses, and record shops from Kenmore Square to Quincy Market sold copies as quickly as they arrived. Taxi struck a chord with working-class families who recognized their own struggles in its story and with students who admired its lyrical craft. Boston embraced the song first, and that embrace gave it the strength to spread nationally. Chapin himself later acknowledged the importance of Boston radio in breaking the record, crediting the city’s DJs and stations for giving his work the early push it needed.

That moment became the spark. Chapin’s talent carried him forward, but it was JC’s instinct and his platform at WMEX that ignited the firestorm. JC had an uncanny gift for recognizing artists who could speak to the heart of a generation, and in Chapin he saw a songwriter whose honesty would endure. Boston, with its immigrant backbone, Irish resilience, and restless student population, was the perfect audience for that breakthrough. JC knew it, and his decision to champion Taxi gave Chapin his first true stage. The record climbed to No. 24 on the Billboard Hot 100, marking the beginning of Chapin’s rise.

By the time WOLD reached audiences in 1973, the groundwork had already been laid. The song charted at No. 36 on the Billboard Hot 100 and carried the voice of every DJ who had lived the life JC had described to Chapin. It echoed those first conversations in Boston, and it became one of the most honest portraits of radio ever written. For Chapin, it was a work of art. For JC, it was proof that his instincts, his bond with Boston, and his willingness to trust the city’s ear had shaped not only a single song but also the beginning of an artist’s legacy.

This was only one example of the reach and responsibility that came with WMEX’s title as the “New Music Authority,” a position JC used again and again to launch artists whose music would come to define an era.

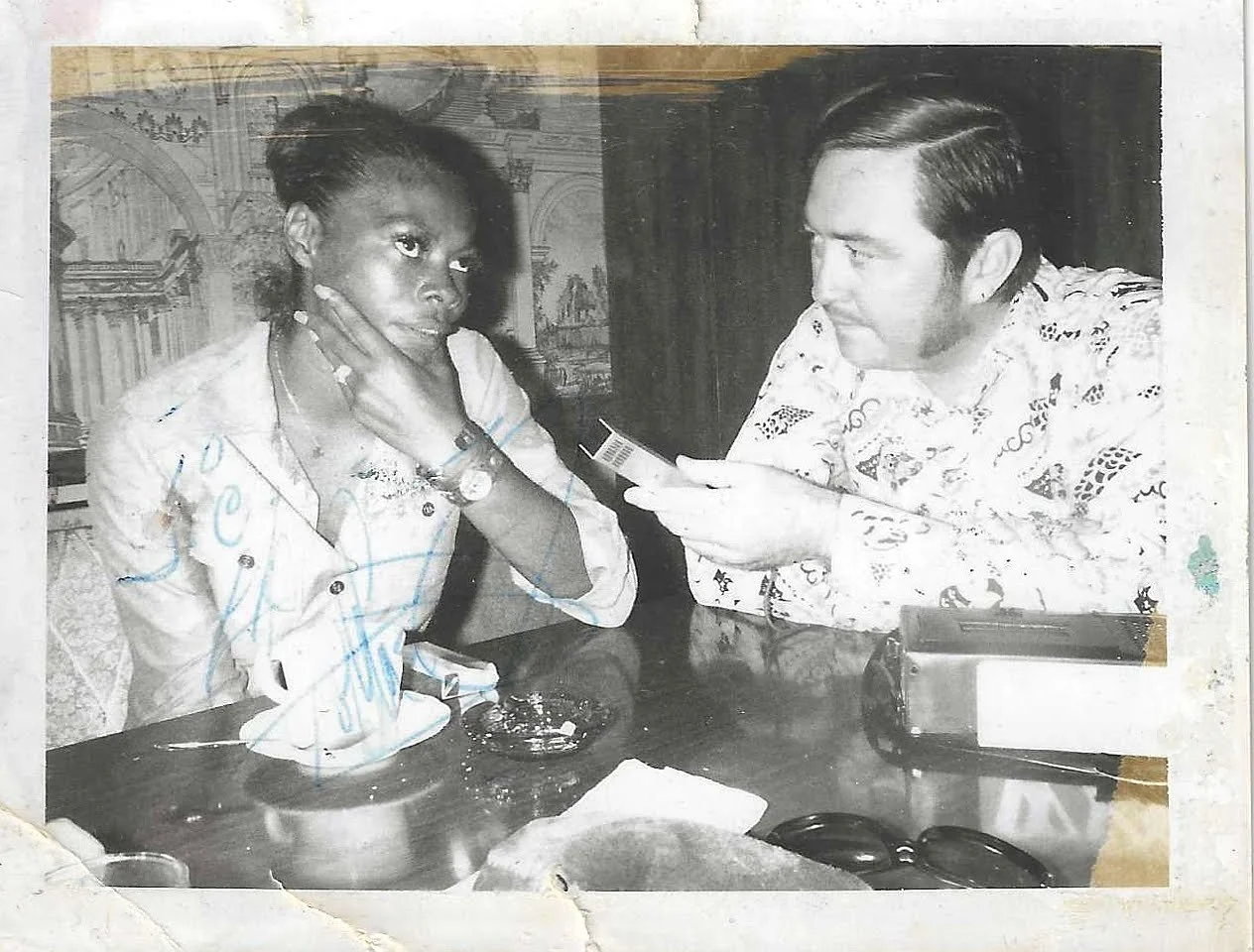

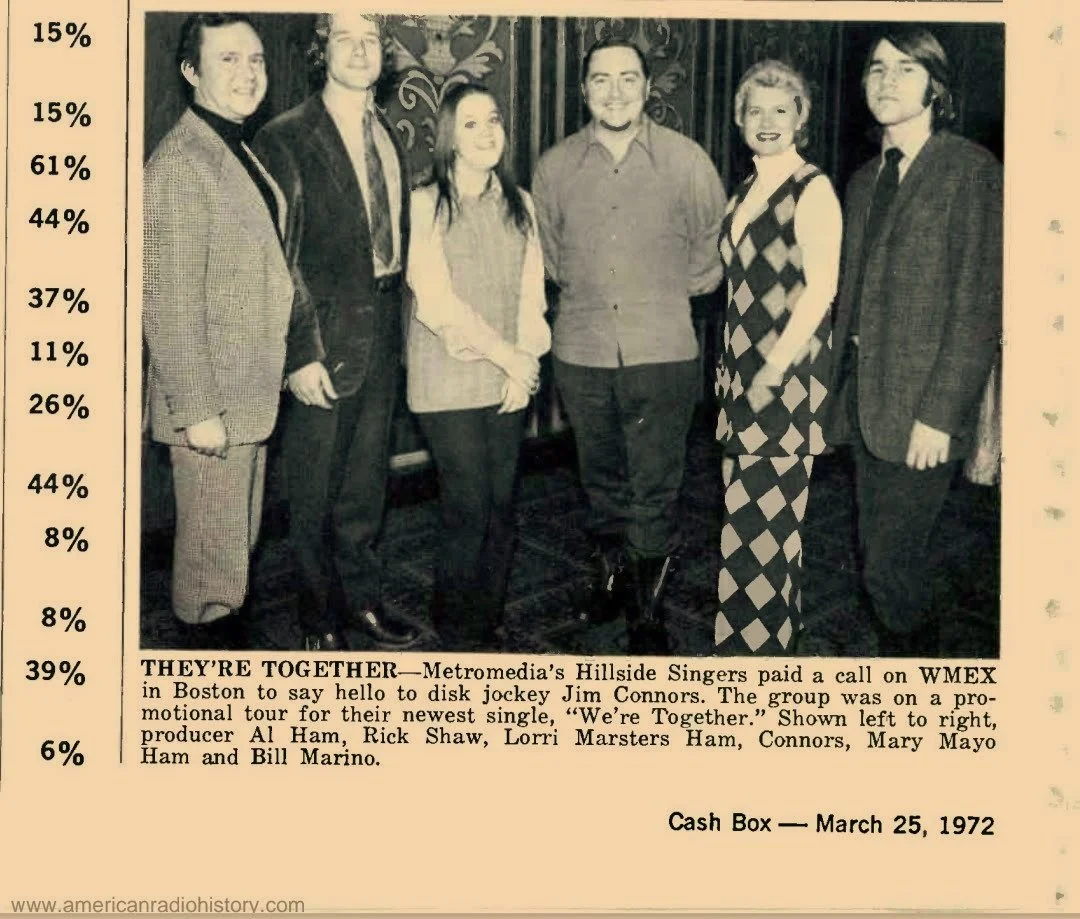

1971 – JC Brings Mouth & MacNeal to American Audiences

At WMEX in Boston, Jim Connors, known as JC, played a decisive role in introducing Mouth and MacNeal to American listeners. The Dutch duo, Willem Duyn with his booming baritone and Maggie MacNeal with her smooth, melodic voice, were paired by producer Hans van Hemert and quickly built momentum across Europe. Their 1972 single How Do You Do became a runaway success, reaching number one in the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, and South Africa, with sales exceeding one million copies overseas.

For the United States, the record was distributed under the Grammophon Philips Group through Polydor and Philips Phonografische Industrie, with United Artists arranging American distribution. This was before PolyGram’s formal consolidation in 1972, and promotion for international acts in the United States was cautious. Records not tied to Britain or Canada were rarely given strong support, and many program directors doubted that a Dutch act could break into the American Top 40.

JC thought otherwise. As Program Director at WMEX, Boston’s “New Music Authority,” he had the instincts and the platform to give the song a fair shot. He placed How Do You Do into steady rotation, introduced it with conviction, and treated it as a record worth attention rather than a passing novelty.

The response in Boston was immediate. Students at Harvard, MIT, and Boston University carried the song across campuses. Families in Dorchester, South Boston, and Quincy phoned WMEX to request it. Record shops from Harvard Square to downtown Boston reported surging sales. JC shared these results with label representatives, proving that Boston audiences were responding, and those numbers gave the Grammophon Philips team the confidence to expand the record’s reach.

By the summer of 1972, How Do You Do had climbed to number eight on the Billboard Hot 100, spent nineteen weeks on the chart, and sold more than a million copies in the United States, earning RIAA gold certification. The success also pushed the album of the same name onto the Billboard 200, where it peaked at number seventy seven. For Mouth and MacNeal, it was their first and only major American hit, one that gave them recognition beyond Europe and set the stage for their 1974 appearance at the Eurovision Song Contest with I See a Star.

Both Willem and Maggie later reflected on how deeply the American response affected them. Maggie described American fans as unusually warm and personal in their reactions, often sharing how the record lifted their spirits during a turbulent era. Duyn put it more simply but with equal weight: “America sang the song back to us.”

For JC, the success meant another gold record on his wall and clear evidence of his ability to recognize international talent before the rest of the market caught on. He understood how to use WMEX’s credibility and his own network to turn Boston’s enthusiasm into national momentum. How Do You Do remains a case study in how one program director’s judgment and presence could change the course of an artist’s career and bring a European act into the center of American pop culture.

1972 – JC Pushes Chuck Berry’s My Ding a Ling Through Controversy to Number One

For Jim Connors, known to his listeners as JC, Chuck Berry had been more than an artist. As a boy, he played Berry’s records constantly, from The Twist to Johnny B. Goode and Roll Over Beethoven. The riffs, the beat, and the humor in Berry’s lyrics shaped JC’s sense of what music could be. Those songs fueled his love for radio and carried forward into his career behind the microphone.

By 1972, Berry was already a legend. His influence on the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and generations of rock musicians was undisputed. Yet despite that legacy, he had never reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100. That changed with My Ding a Ling, a live recording made at the Lanchester Arts Festival in Coventry, England, and released on The London Chuck Berry Sessions.

The song was playful, built on call and response with the audience, and laced with sly double meanings. Its release immediately divided opinion. Critics dismissed it as a novelty. In Britain, activist Mary Whitehouse called on the BBC to ban it, claiming schoolchildren were singing it “with their trousers undone.” In the United States, schools and community groups raised similar complaints, and some stations in New England refused to play it.

JC saw it differently. As Program Director of WMEX, Boston’s “New Music Authority,” he gave the song steady airplay and introduced it with genuine admiration for Berry. His credibility made listeners take it seriously when other programmers hesitated. Boston responded in force. Requests poured in to WMEX. Students at Harvard and MIT sang it across campuses. Families in Dorchester, Quincy, and South Boston called in asking for it. Record shops in Kenmore Square and downtown Boston reported they could not keep it in stock.

JC relayed the results to Chess Records. Marshall Chess, son of founder Leonard Chess and a vice president at the label, was determined to push the single further. With Boston showing strong numbers, the label expanded its campaign, and other program directors followed WMEX’s lead.

The payoff was historic. In October 1972, My Ding a Ling reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100, holding the top position for two weeks and spending nineteen weeks total on the chart. It sold over one million copies in the United States and earned RIAA gold certification. Across the Atlantic, the record entered the Official U.K. Singles Chart at number thirty eight on October 22, 1972, and climbed to number one four weeks later. It remained at the top for four consecutive weeks in November, making it Berry’s only number one hit in Britain as well as in the United States.

The success of the single also lifted The London Chuck Berry Sessions album, which climbed to number eight on the Billboard 200 and reached the U.K. top ten, giving Berry his strongest album performance in years. JC received a gold record for his role in the single’s success. Chess Records even offered him the chance to relocate to England and work more closely with the label, an opportunity he declined in order to remain close to his family. He often reflected on how different his career might have been had he gone, but he valued staying rooted at home.

This chapter carried even deeper meaning when seen alongside Berry’s wider legacy. Earlier classics like Johnny B. Goode had already been enshrined, earning a place in the Grammy Hall of Fame and later selected for the Voyager Golden Record, launched into space in 1977 to carry humanity’s greatest cultural achievements beyond the solar system. JC’s direct role in promoting Berry’s only number one single meant that he, too, had helped strengthen the artist’s standing at the very moment his legacy was being secured for eternity. Behind the scenes, JC also used his industry ties to encourage recognition of Berry’s influence, conversations that echoed in how those selections were framed.

For JC, helping Chuck Berry finally claim the chart crown was both a personal and professional triumph. As a boy, he had worn out Berry’s records. As a broadcaster, he helped his idol reach the top of the charts and reinforced his place as one of music’s immortals. It was proof that a program director’s conviction and credibility could shape careers, silence critics, and help ensure that an artist’s music would live on not just in gold records on a wall, but on a golden record sent into the stars.

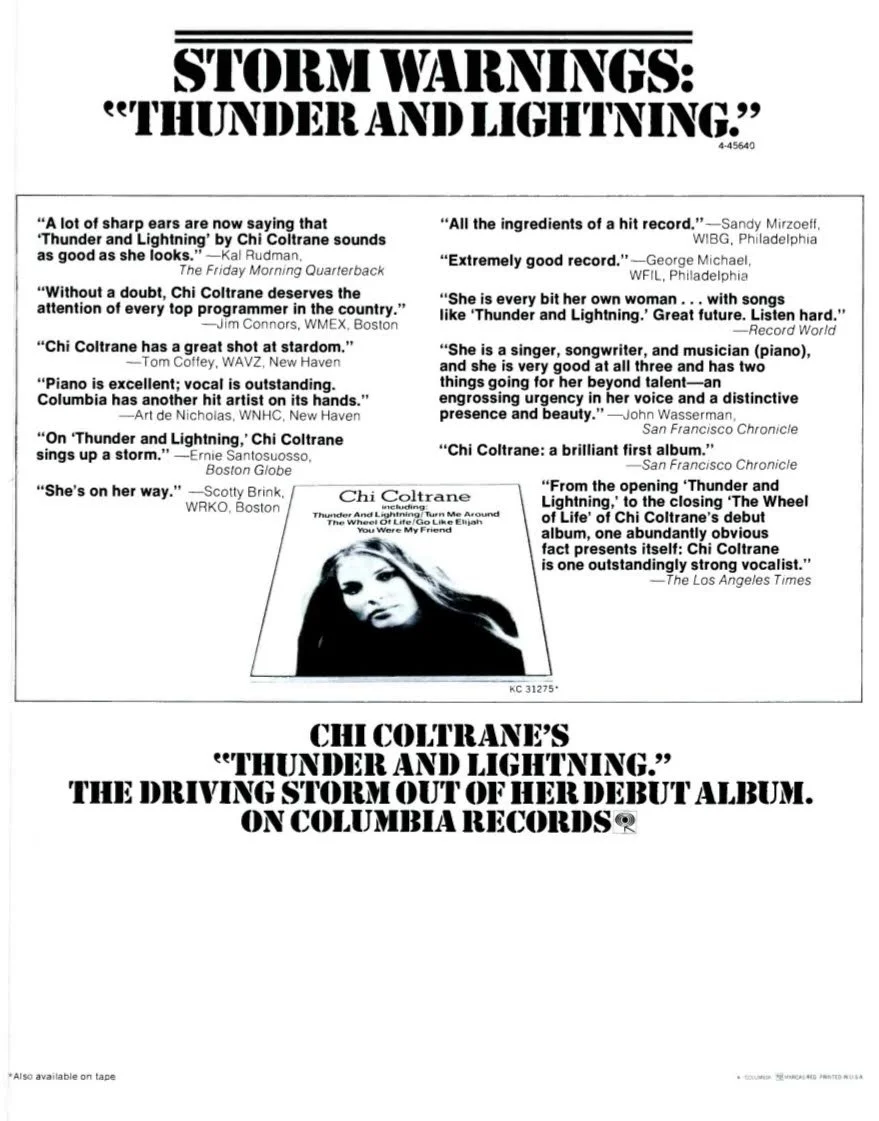

1972 – JC and Columbia Records Break Chi Coltrane’s “Thunder and Lightning”

When Columbia Records president Clive Davis signed Chi Coltrane in 1972, he was convinced she was a star in the making. After hearing her demo, he flew her to New York, and before she had finished her first audition song, Davis stopped her and offered a contract on the spot. Bob Altshuler, Columbia’s Vice President of Publicity and a Boston native, added further weight. Altshuler, who had graduated from Boston English High and Boston University, knew Boston radio was often the ignition point for breaking new acts. Together, Davis and Altshuler made Coltrane’s self-titled debut album a priority, and its lead single, Thunder and Lightning, became the test case.

At WMEX in Boston, Jim Connors — JC — was immediately taken by Coltrane’s talent. Her piano-driven sound was fierce, her vocals urgent, and her stage presence magnetic. Unlike the softer tones of Carole King or Elton John, Chi attacked the keys with the fire of Jerry Lee Lewis while blending gospel, rock, and classical flourishes. JC heard something fresh and believed his listeners would, too. He put Thunder and Lightning into heavy rotation, introduced it with conviction, and framed Coltrane not as a hopeful but as a major new voice.

The city lit up. Requests poured into WMEX from neighborhoods in Dorchester, Quincy, and South Boston. Students at Harvard, MIT, and Boston University passed the single through campus bars and dormitories. Record shops in Kenmore Square and Harvard Square sold out, with Columbia hustling to keep stock flowing. Coltrane herself visited Boston on a promotional tour, and WMEX’s backing amplified her appearances. JC didn’t stop at Boston; he called fellow program directors in New York and Connecticut, pointing to WMEX’s numbers. Within weeks, the momentum stretched down the Northeast corridor, convincing New York programmers that Boston’s buzz was real.

By November 1972, Thunder and Lightning had climbed to number 17 on the Billboard Hot 100, where it stayed for thirteen weeks. It was a solid national debut, and Columbia recognized JC’s contribution with a gold record, adding another plaque to his growing collection. For him, it was proof that Boston’s credibility could ripple into New York and beyond, and that his instincts about Coltrane had been right.

Yet Chi Coltrane’s story did not end in the United States. While Thunder and Lightning made her a one-hit wonder in America, Europe embraced her as a star. In Germany, the single reached number 4, and she went on to score multiple top-five hits, including The Wheel. She was voted “Top Female Artist” in Germany for two consecutive years, dubbed “The Queen of Rock” by European media, and held the top spot in the Musik Express Popularity Poll. In the Netherlands, her single Go Like Elijah became a national phenomenon, holding the number one position for a full month in 1973. She released albums specifically for European labels, built a long residency on the continent, and even when she returned to performing decades later, her tours in Germany and the Netherlands sold out.

Coltrane’s powerful vocals, gospel influences, and fiery piano style made her a fixture on European stages in a way she never quite achieved at home. She was showered with awards, including the European Gold Hammer and Silver Hammer for “Top Female Artist,” and she was later listed among the “100 Best Musicians of the Century” in Europe.

For JC, being part of her U.S. breakthrough was still meaningful. He had taken a record he believed in, pushed it through the Boston market, and watched it ripple across the corridor into national charts. He understood her career would ultimately thrive more in Europe, but in 1972, it was his ear, his conviction, and his platform at WMEX that gave her and Clive the start they needed to influence and push into the market.

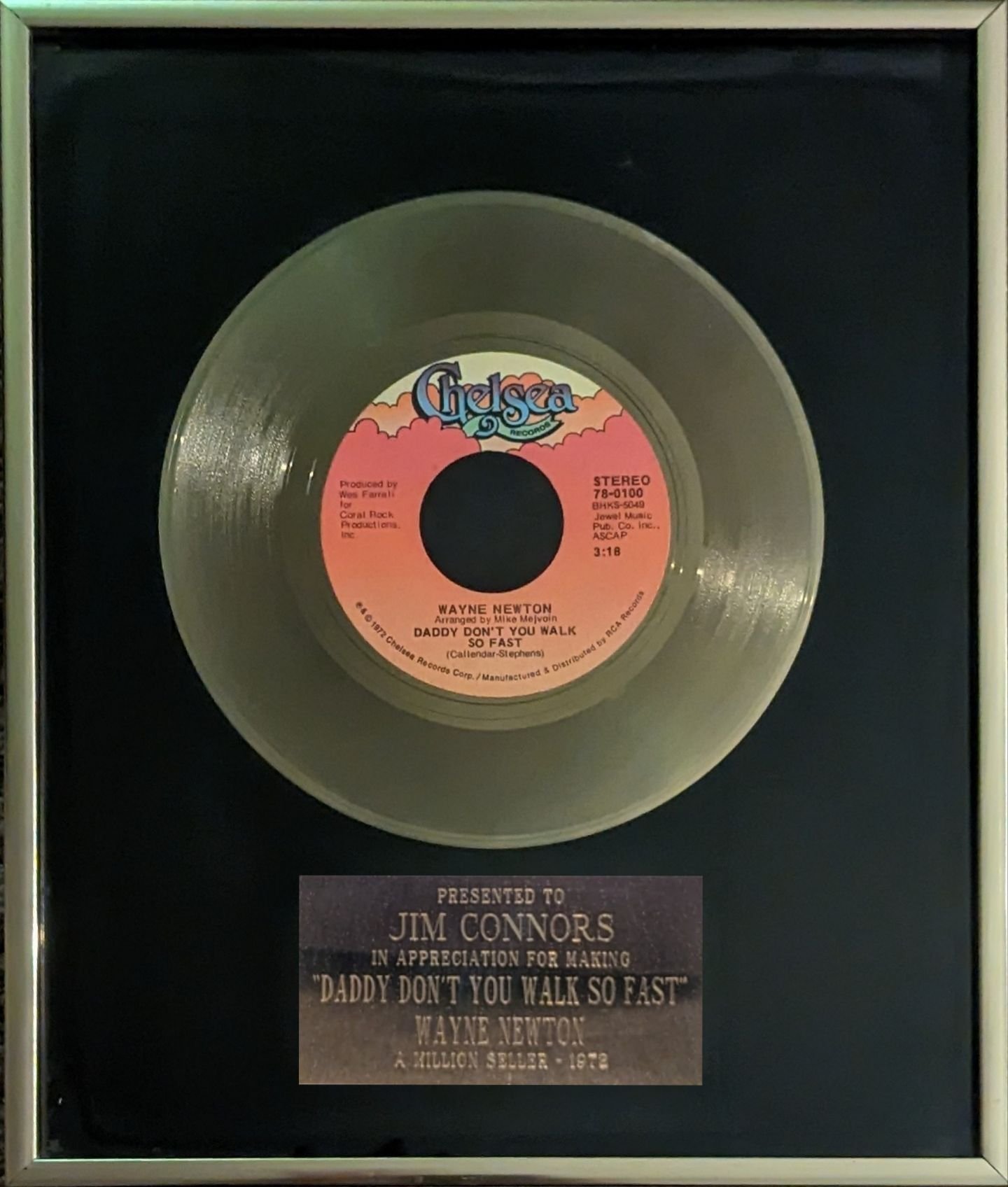

1972 – JC Helps Launch Wayne Newton’s Biggest Hit

In 1972, Wayne Newton recorded Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast, written by Peter Callander and Geoff Stephens. The song tells the story of a father leaving his family, only to hear his daughter call after him, asking him to slow down and come back. Its message of loss, regret, and reconciliation carried emotional weight that listeners across generations understood.

Newton first heard the song through Daniel Boone’s 1971 version in the United Kingdom and said it gave him goosebumps. His label at the time, Capitol Records, refused to let him record it. One executive even called it “the worst song I’ve ever heard.” Newton walked away from Capitol and became the first artist signed to Wes Farrell’s new Chelsea Records. Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast was Chelsea’s debut release, and its success would determine whether the label had a future.

Radio made the record. Rosalie Trombley at CKLW in Windsor and Detroit added it early, and the single caught fire in the Midwest. In Boston, Jim Connors — JC — recognized both the strength of the song and its personal resonance. Separated from his wife and children in Erie, Pennsylvania, he felt the lyrics in his own life. When he introduced the record on WMEX, Boston’s “New Music Authority,” that conviction came through. Listeners responded immediately. Requests poured in from Dorchester, Quincy, and South Boston. Students across Cambridge carried it through dorms and campus bars. Record stores in Kenmore Square and downtown Boston sold out.

JC was more than a voice on the air. He worked closely with Chelsea’s regional promotion team, relayed Boston’s results back to New York, and called on his network of program directors throughout New England. He knew how to use his influence, his personality, and his relationships to turn one station’s success into momentum across the corridor. The teamwork between Newton, Chelsea, and WMEX turned Boston into one of the record’s strongest early proving grounds.

The results were undeniable. Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast climbed to number four on the Billboard Hot 100, reached number one on the Cashbox chart for the week of August 5, 1972, and even crossed into the Billboard country chart at number fifty five. It sold more than one million copies in the United States and was certified Gold by the RIAA. Internationally, the record went to number one in both Canada and Australia. While Daniel Boone’s version had charted in the United Kingdom, it was Newton’s recording, fueled by radio support in markets like Boston, that gave the song global reach.

Newton himself later reflected on the importance of Boston: “Boston, and the towns close by, have been such an important part of my life and career. They were really the first people that took us in and took notice and really treated me like they wanted to see me again.” He also admitted that the single had come at the right time, saying it “saved his career” after years of being seen mainly as a Las Vegas headliner.

For JC, Chelsea presented him with a gold record in recognition of his contribution, but the deeper validation was in knowing that Boston had mattered. For Newton, the song gave him a second act beyond the Vegas strip, proving he was more than a showroom entertainer. And for Wes Farrell, the record gave Chelsea Records the credibility to grow. Within a few years, the label was releasing gold and platinum records by Jim Croce, Tony Orlando and Dawn, and Bill Withers. The foundation for that success was laid when Newton’s single broke through in Boston.

The story of Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast showed how success in the early seventies depended on teamwork and trust. It was not just a hit song but the convergence of an artist determined to be heard, a new label willing to take a risk, and a program director in Boston who knew how to connect records, listeners, and the industry. JC was a master of that craft.

1972 – JC Helps Joe Simon’s “Power of Love” Rise on the Charts

By 1972, Joe Simon was already one of the most distinctive voices in American soul. Born in Simmesport, Louisiana, he grew up singing in his father’s Baptist church before his family moved to California, where he joined the Golden West Gospel Singers. His deep baritone, blending gospel fire with the storytelling of country and southern soul, set him apart in the 1960s with hits like The Chokin’ Kind and Your Time to Cry. Simon earned his first Grammy in 1970, and by the early seventies he was entering a new creative phase.

That phase came through Spring Records, a new independent label founded in New York by Roy and Julie Rifkind with Bill Spitalsky. Distributed through Polydor, Spring made a bold move by pairing Simon with Philadelphia’s Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. Together they brought Simon into the emerging “Philly Soul” sound — polished production, lush orchestration, and arrangements that carried gospel emotion into a crossover market.

The first product of that collaboration was Drowning in the Sea of Love in 1971, a million-seller that re-established Simon’s commercial strength. The follow-up, Power of Love, released in 1972, became his biggest hit. Written by Gamble and Huff, it was a song of resilience and redemption, a statement about love as a force that could carry people through hardship. Simon’s performance gave it conviction, and the production gave it polish fit for both R&B and Top 40.

At WMEX in Boston, Jim Connors — JC — immediately recognized the record’s potential. Boston was not always seen as an R&B city, but JC knew how to read a record that could bridge communities. He added it into rotation on WMEX, introduced it with authority, and the response was immediate. Requests poured in from Dorchester and South Boston. Students at Boston University and MIT played it in dorms and local bars. Record shops in Kenmore Square and downtown reported fast sales.

JC’s value was not only what he did on air but how he worked the business. He kept close ties with Spring’s promotion staff, shared Boston’s strong results back to Polydor’s distribution team, and leaned on his network of program directors across the Northeast. Through his “Think Sheet,” a short industry paper he circulated among peers, JC highlighted Power of Love and encouraged other stations to move on it. His influence even reached as far as Scott Shannon and the staff at WMAK, who respected JC’s instincts and followed his leads.

The results spoke loudly. Power of Love hit number one on the Billboard R&B chart, stayed there for two weeks, and peaked at number eleven on the Hot 100. It sold more than one million copies and was certified Gold by the RIAA. Simon also won the 1973 Grammy for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance, his second career Grammy, confirming the song’s artistic and commercial impact.

For Joe Simon, it was a career-defining moment that secured his place as one of the great soul voices of the seventies. For Spring Records, it proved that a small independent, with Polydor’s distribution muscle, could stand alongside Motown and Atlantic in breaking national hits. For JC, the gold record he received was recognition of his role in taking a Philadelphia-crafted soul single and making it resonate in Boston, then using that spark to help fuel national momentum.

Simon would go on to write the theme for Cleopatra Jones in 1973 and score another number one R&B hit with Get Down, Get Down (Get on the Floor) in 1975, before eventually leaving secular music for ministry. But in 1972, with Power of Love, his career reached its peak — and WMEX, with JC at the helm, was part of the team that made it happen.

The story of Power of Love was not about one man alone. It was about an artist with a voice of conviction, producers with the right sound, a label and distributor willing to push, and a program director in Boston who knew how to turn local response into national results. JC was a master at that craft, and Joe Simon’s success became one more gold record that proved it.

1973 – JC Helps Clint Holmes Score His Breakthrough Hit

In 1973, Clint Holmes reached an unexpected pinnacle with Playground in My Mind, a record unlike anything else on the charts at the time. Written and produced by Paul Vance and Lee Pockriss, the single had a childlike refrain sung by Vance’s seven-year-old son, Philip. Its nursery-rhyme simplicity, with the line “My name is Michael, I’ve got a nickel,” tapped into nostalgia and innocence at a time when most of the charts leaned on soul, hard rock, and disco.

Holmes, born in Bournemouth, England in 1946, was raised in Farnham, New York, a small village southwest of Buffalo. The son of a Black American jazz musician and an English opera singer, his musical roots ran deep. He often said, “my mom taught me how to sing correctly and my dad taught me how to enjoy it.” After serving in the U.S. Army Chorus during the Vietnam era and working Washington D.C. nightclubs, Holmes was discovered by Paul Vance while performing in the Bahamas. A first recording of the song on Atlantic Records had gone nowhere, but Epic Records, a Columbia subsidiary, gave it a second chance.

At WMEX in Boston, Jim Connors — JC — understood the song’s potential better than most. Boston was a market with both grit and sensitivity, and JC knew his audience would recognize the sentiment. He put the record into steady rotation, framed it as more than novelty, and spoke about it with conviction. Listeners across Boston, from Dorchester and Quincy families to Cambridge students, embraced it. Record stores in downtown Boston and Kenmore Square sold through copies quickly.

JC’s instincts and influence mattered. He worked Epic’s promotion team, sharing the strength of Boston’s response with their New York executives, and spread word through his “Think Sheet,” a paper he circulated among program directors. Other stations, including Johnny Holliday at WWDC in Washington, soon picked it up, and the song began its climb nationally.

The momentum became unstoppable. Playground in My Mind spent 23 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at number two in June 1973, held back only by Paul McCartney and Wings’ My Love. It sold more than one million copies, was certified Gold, and became a major international success. In Canada, it reached number one and held the top spot for three weeks. While some critics dismissed it as saccharine, audiences embraced its innocence and escape, and its legacy has endured for decades. A shortened version was even used in the 2024 film IF, reminding new generations of its charm.

Holmes himself later admitted that Playground in My Mind made him a one-hit wonder on the charts, but he also said its impact could not be denied. It gave him national recognition, a Gold record, and the chance to build a long career as one of Las Vegas’s most enduring headliners.

For JC, Epic Records presented him with a Gold record in gratitude, a marker of his role in moving an unconventional single from Boston to national prominence. It was another example of his craft, not just spinning records, but recognizing when a song could connect, giving it the right support on air, and navigating the business relationships that turned local response into national success.

Playground in My Mind was a reminder that the business of radio in the early seventies was as much about instinct and influence as it was about playlists. For Clint Holmes, it created a career. For Epic, it proved that risks could pay off. And for JC, it was one more success that showed Boston radio could help change the national charts.

1973 – JC and Harry Chapin’s “W.O.L.D”

In 1973, Harry Chapin released W.O.L.D on his album Short Stories, a song drawn directly from his conversations with Jim Connors — JC — and from the lived reality of radio men. Chapin framed the lyrics as the story of a DJ who gave everything to his career and lost much along the way. The refrain about “feeling all of forty-five, going on fifteen” captured the strange contradiction of having to sound forever young while carrying the weight of age, travel, and broken family ties. For those inside the industry, it was more than fiction; it was recognition.

JC knew it immediately. As Program Director and morning drive voice of WMEX in Boston, he had lived the constant grind and personal sacrifice Chapin described. WMEX was not just another station; it was Boston’s “New Music Authority,” a platform that could give a record credibility across the Northeast. JC put W.O.L.D on the air, introduced it with conviction, and Boston listeners responded. From Cambridge to Quincy, the record carried weight because it sounded true.

The single became a modest chart success in the United States, reaching number 36 on the Billboard Hot 100 in March 1974, number 26 on Cash Box, and number 28 on Record World. In Canada, it reached as high as number 9, and in the United Kingdom it climbed to number 34. Across Europe and other markets it earned top-20 positions, and by the end of its run W.O.L.D had sold more than one million copies worldwide. Despite Chapin’s later jokes that it charted “for 15 minutes,” it stood as one of his most recognizable songs, and one of the few hits that turned a working DJ’s life into art.

For JC, the recognition was tangible. Chapin’s song mirrored his own sacrifices and those of his peers, and a gold record plaque was presented to him in appreciation. Like many DJs of the era, this was an “in-house” award, the type of commemorative presentation that record labels often produced for radio figures, record store owners, and distributors who helped drive a hit. While not the same as an RIAA-certified disc, these awards were a respected industry tradition and a marker of JC’s influence. It was a reminder that his life in broadcasting was not just about programming or breaking artists, but about inspiring a piece of music that told the truth about his profession.

In Boston, W.O.L.D was more than a record. It was a reflection of the city’s radio culture, where listeners cared deeply about the voices behind the microphone. And for JC, it marked a rare moment when his work as a broadcaster crossed into the world of songwriting, leaving behind a permanent, musical record of the life he lived.

1972 – Harry Chapin’s “Taxi” and JC’s Early Support

Harry Chapin’s breakthrough came with Taxi, released in 1972 on his debut album Heads & Tales under Elektra Records. At over six minutes long, the song was unconventional for AM radio, but its power came from Chapin’s gift for storytelling. It followed a San Francisco cab driver, once a dreamer who wanted to fly, who picks up his former lover and confronts how their lives had diverged. She had dreamed of acting, he of flying, yet both had settled into compromises, reflecting on what was gained and what was lost.

Chapin debuted Taxi on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in April 1972. The audience response was so overwhelming that Carson broke tradition and invited him back the very next night, giving Chapin a rare and decisive career breakthrough. The single climbed to number 24 on the Billboard Hot 100, spent 16 weeks on the chart, peaked at number 5 in Canada, and ranked as one of the top songs of the year. Both the single and the album eventually sold more than a million copies.

Boston was one of the first markets to truly embrace Taxi. At WMEX, Jim Connors — JC — immediately recognized how unusual and compelling the record was. Instead of treating its length as a liability, he framed it as a story worth hearing and gave it steady rotation. Rival station WRKO followed suit, and by April 1972 Taxi had reached number one on both Boston charts. This early momentum in New England helped fuel its national rise.

JC was presented with a gold record plaque for his part in helping to break Taxi. Like many awards of that era, it was an “in-house” presentation from the label — a way Elektra recognized disc jockeys, program directors, and record stores who contributed to a record’s success. While not the same as an RIAA-certified disc, these awards were an industry tradition and a genuine acknowledgment of influence. For JC, it was less about personal glory than about being part of the team that brought an extraordinary songwriter to a wider audience.

Taxi established Harry Chapin’s reputation as a master of long-form narrative songwriting and earned him a Grammy nomination for Best New Artist. For JC, the song was more than just a hit; it was proof that radio could connect listeners with something deeper, and that Boston’s voice in the music industry carried weight far beyond New England.

1973 – Jim Croce’s “Time in a Bottle” and JC’s Memorial Award

Jim Croce’s Time in a Bottle began as a private love song. He wrote it in December 1970 after his wife Ingrid told him she was expecting their son, A.J. The recording came together with a harpsichord that happened to be in the studio, giving the track a unique, almost classical sound that matched its theme. The lyrics reflected a wish to capture time and save it for the people who matter most. The song first appeared in 1972 on the album You Don’t Mess Around with Jim.

Its meaning grew heavier after Croce’s death in a plane crash in Natchitoches, Louisiana, on September 20, 1973. He was only thirty years old. The crash killed Croce, his guitarist Maury Muehleisen, comedian George Stevens, two members of his tour staff, and the pilot. An investigation later concluded that the pilot, who had advanced heart disease and had been rushing to make the flight, failed to clear a pecan tree during a foggy takeoff.

In the days after the crash, radio stations around the country began playing Time in a Bottle in tribute. The demand was so strong that ABC Records released it as a single in November 1973. The record entered the Billboard Hot 100 on November 17 and climbed to number one by December 29. It stayed there for two weeks and sold more than a million copies. Croce became only the third artist to reach the top of the chart after his death, following Otis Redding with Dock of the Bay and Janis Joplin with Me and Bobby McGee. The surge in interest also pushed You Don’t Mess Around with Jim to number one on the album chart.

In Boston, Jim Connors — JC — gave the song an important push. At WMEX, a station already known as the city’s “New Music Authority,” JC placed Time in a Bottle into heavy rotation. Boston’s audiences, with their strong appreciation for storytelling in song, connected immediately to Croce’s words. WMEX’s early and consistent support during those weeks after Croce’s death helped carry the record from local airplay into national prominence.

ABC Records later presented JC with a memorial plaque in thanks. Rather than the standard RIAA-certified disc, it was an in-house award produced by Disc Award Ltd., a company that created high-quality plaques for radio personalities and industry figures who played a role in breaking records. The Time in a Bottle award featured a gold-plated record mounted on black velvet under glass, etched with the manufacturer’s distinctive “dragon” mark. These awards were not official certifications but tokens of appreciation, and in time they became prized pieces of music history.

For JC, this award stood apart from the others. It represented not only a number one record but also the memory of an artist whose life ended far too soon. Time in a Bottle remains one of Croce’s most enduring works, and for JC it was a reminder of how radio could carry a voice beyond tragedy and preserve it for generations.

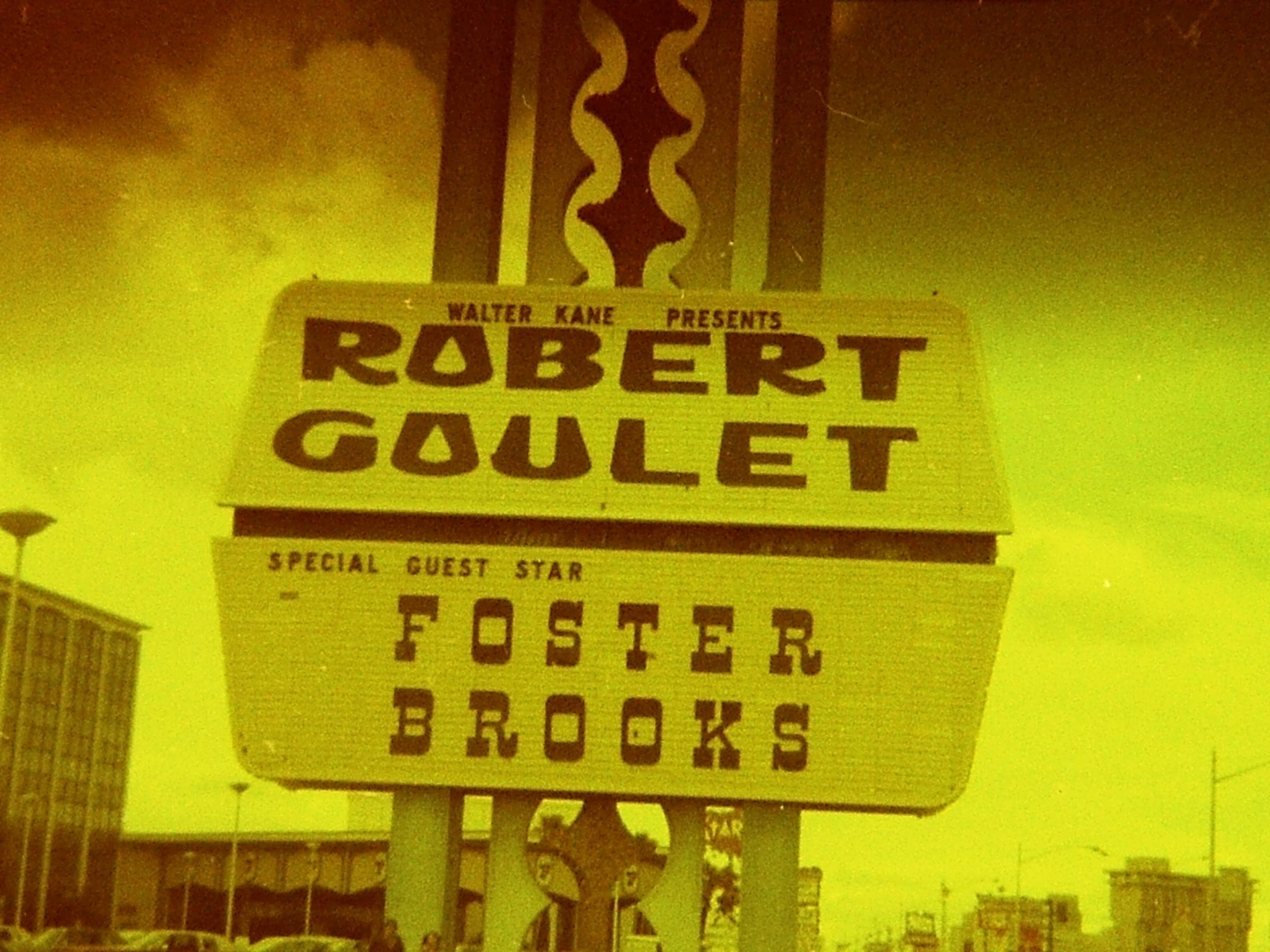

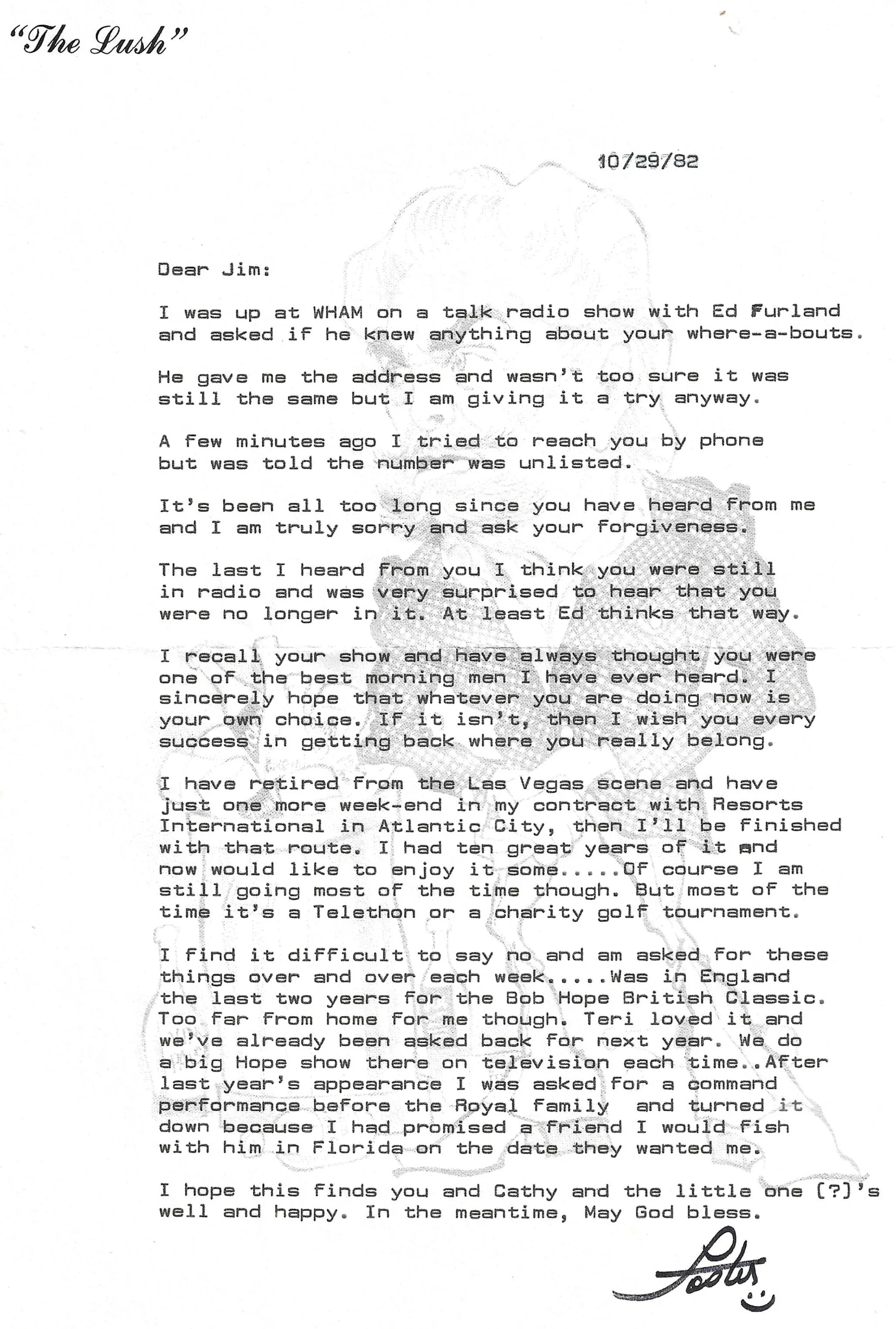

1973 – JC and Foster Brooks: A Lasting Friendship

In 1973, Jim Connors and Foster Brooks became friends, beginning a bond that would carry through the years. Foster, best known for his “Lovable Lush” character on The Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts and variety shows, was one of the sharpest comic minds of his time. Away from the stage, he was thoughtful, disciplined, and very different from the inebriated figure audiences saw. JC recognized that difference right away, and what started as a professional introduction grew into a genuine friendship.

Whenever Foster came to Boston, he and JC made time to be together. They shared meals, swapped stories, and filled conversations with the kind of humor that made both of them successful in their fields. Their styles were similar, quick and clever, built on timing and observation. JC admired Foster’s ability to turn a pause or misplaced word into laughter, while Foster valued JC’s natural gift for connecting with people and keeping the mood easy.

They stayed in touch through letters, phone calls, and visits. Busy schedules never dimmed the bond. Each found in the other someone who understood the pressures of entertaining audiences, but also someone who knew how to keep it fun. They encouraged each other, traded jokes to ease long days, and offered friendship rooted in respect as much as in laughter.

Both men were influential in their own ways, Foster as a comedian who became a household name and JC as a broadcaster who brought new music and voices to the public. Their friendship bridged those worlds. JC often said he loved Foster not only for the laughter he brought but for the loyalty and warmth behind it.

For JC, the friendship with Foster Brooks was a constant, a reminder that even in the fast moving world of entertainment, the best relationships were the ones that endured.

WYSL Buffalo

Jim Connors & Harry Chapin discuss WOLD and TAXI

1974 – JC at WYSL Buffalo: Reinvention, Resilience, and Regional Power

By 1974, Jim Connors had lived through the whirlwind of Boston’s WMEX years. He had helped launch records, built national relationships, and even found himself in the lyrical crosshairs of Harry Chapin’s W.O.L.D. The song, inspired by his experiences and conversations with Chapin, spotlighted the untold sacrifices of disc jockeys — the constant relocations, fractured family ties, and the pressure to always sound young and vital even as real life weighed heavily. For JC, those themes hit painfully close to home. His marriage had unraveled under the strain of separation, and his children remained in Erie, Pennsylvania. He was still a nationally recognized name in radio, but what he wanted most was proximity to his kids and a chance to reclaim a sense of balance.

That opportunity came with WYSL in Buffalo, a station hungry to rise against the dominance of WKBW, the longtime powerhouse led by Larry Anderson and later Jefferson Kaye. WYSL’s owner, Gordon McLendon, had been known nationally as the “maverick” who revolutionized Top 40 radio. By the 1970s, the Buffalo market was one of the most competitive in the country, and WYSL’s leadership understood that a strong morning show could shift the balance. They turned to JC.

Larry Levitt, who was managing WYSL at the time, recognized both the risks and rewards of bringing JC in. Connors carried the aura of his WMEX success, the gold records on his wall, and the reputation for “breaking” artists. He also carried the tabloid attention that followed the release of W.O.L.D. Levitt’s gamble paid off. JC’s arrival in Buffalo was both a personal reset and a professional statement: he was still one of the most commanding voices in American radio.

Buffalo was a city in transition in the 1970s. The steel mills and grain elevators that had defined its skyline were beginning to struggle, but its neighborhoods were still vibrant, its cultural institutions strong, and its people fiercely loyal to radio. JC understood that instantly. He had grown up just a few hours away in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, a working-class town with a proud immigrant backbone. Buffalo felt familiar — Irish, Italian, Polish, and German families, close-knit neighborhoods, and a no-nonsense audience that could spot a phony from a mile away. JC respected that, and in return, the city embraced him.

As the new morning drive host, JC transformed WYSL into a contender. His program mixed national music trends with local sensibilities. He knew how to blend the big names with the community’s heartbeat — one hour he might be introducing a new single from a rising act, the next he’d be talking about the Sabres’ playoff push or the Bills’ chances that season. His interviews drew big names through Buffalo: Wayne Newton stopped by to talk about his chart success, Chuck Berry recalled the early rock years, and Harry Chapin himself reconnected with JC to reflect on the stories behind his songs. For listeners, WYSL’s morning slot became a meeting place — music, news, and personality rolled into one.

JC’s ability to work the phones and cultivate label relationships also gave WYSL an edge. He kept close ties with Columbia, Atlantic, and RCA reps, ensuring Buffalo got records early and often. In those years, radio wasn’t just about spinning songs. It was about proving your market could move sales, and JC knew how to show that Buffalo could. He built relationships with distributors, tracked local record shop orders, and leveraged his industry-wide reputation to make sure national promotions didn’t skip Western New York.

The results were clear. By the mid-1970s, WYSL had climbed past WKBW in certain dayparts, something once thought impossible. For a period, the morning show was the talk of the town, driving not only ratings but also advertising dollars in a fiercely competitive market.

For JC personally, the Buffalo years mattered beyond the microphone. He was closer to Erie, able to see his children more often, and in many ways, able to breathe again. Friends recall that despite the pressures of rebuilding his career and life, he carried himself with energy, humor, and a determination to keep moving forward. The strain of his marriage’s end never left him, but his resilience was evident in how he poured himself into his work and his role as a father.

WYSL ultimately became more than just another station on JC’s résumé. It was the place where he proved that he could rebuild after Boston, that he could still anchor a station in a major market, and that his blend of instinct, personality, and industry savvy was as valuable in Buffalo as it had been anywhere else. His time at WYSL reinforced what made him unique: a broadcaster who combined the instincts of a tastemaker with the heart of a storyteller, someone who could move records and move people in the same breath.

JC’s years at WYSL stand as a reminder that professional achievements and personal struggles often move together. On the surface, he was one of the most successful radio men in the country — a Program Director with gold records on the wall, the influence to move songs nationally, and the reputation of a tastemaker who could shape the sound of a major market. Behind that public success, though, was a man working through the weight of a marriage that had ended, children he longed to see more often, and the scrutiny that came with living in the public eye.

The move to Buffalo was more than a career step. It was an act of resolve. WYSL needed credibility and energy, and JC needed a base where he could both rebuild his professional standing and be closer to Erie, where his children lived. That proximity mattered. Being able to make the drive down the lake on weekends and spend time with his family gave his work renewed meaning. He was not simply chasing ratings; he was anchoring his life around something larger than the job.

Listeners in Buffalo may not have known the depth of his private battles, but they could hear the authenticity in his voice. His broadcasts carried the energy of a veteran entertainer and the empathy of someone who had lived through real change. This made him relatable. He could spin a hit, joke with a guest, or light up the phone lines, but he could also add a moment of reflection that reminded people that the man behind the microphone was as human as they were.

WYSL became a proving ground not only for ratings but for resilience. JC managed to rebuild his stature in one of the toughest radio markets in the country while also centering himself as a father and as a man determined not to lose sight of what mattered most. His story in Buffalo illustrates what many in the entertainment world live quietly…that the drive to succeed professionally often collides with the need to heal personally.

By the mid 1970s, JC had achieved both. He gave WYSL credibility against its rivals and at the same time carved out space to reconnect with his family. In doing so, he showed that personal resolve and professional dedication are not separate forces but part of the same story. His time at WYSL was not about reinvention for its own sake. It was about survival, balance, and the belief that even in the face of setbacks, a person can move forward with purpose.

1975: JC Steadies WROC Through Strikes, Struggles, and Local Stardom

In 1975, JC began a new chapter at WROC in Rochester, New York. He and his second wife were preparing for the birth of their first child, and the move brought him closer to his New England roots. For JC, WROC offered both a professional opportunity and a chance to settle into family life while staying connected to a region he loved.

The station he joined was in a turbulent position. WROC television, Channel 8, had fallen behind its local rivals WHEC and WOKR in the ratings. Once a strong NBC affiliate, it now sat in a distant third place. WROC radio, at 950 on the AM dial, was struggling even more as FM music stations like WCMF and WPXY were winning over younger audiences. It was a competitive and unforgiving environment, but it also gave JC a chance to prove his adaptability.

Almost immediately, WROC was caught in the middle of a labor dispute. Members of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists walked off the job in protest of pay cuts and worsening conditions. Picket lines formed outside the Humboldt Street studios, drawing attention in the local press. With the newsroom short-staffed, managers scrambled to keep programming on the air. JC stepped in wherever he was needed, not only holding down his regular duties but also taking on extra work. At one point he even delivered weather segments on television, filling in so that viewers would continue to receive daily news and forecasts. His willingness to adapt and cover gaps showed the same resilience that had carried him through earlier stages of his career.

In the midst of these challenges, JC reminded audiences that radio could still be fun. On April 1st, 1975, he staged an April Fool’s prank with George Beahon, the outspoken sports commentator from Channel 13. After the morning news, Beahon went on the air pretending to be Connors, cracking jokes and singing as if he were the morning host. The switchboard lit up with calls from confused listeners, some convinced that JC was experimenting with his voice. At 9:10 a.m., JC came on to reveal the gag, laughing that Beahon’s sharp sports commentary often made people want to “kick in their television sets,” so it was only fair to give radio listeners the same feeling. The prank became a well remembered local story, showing JC’s knack for humor and his ability to connect with audiences beyond the music.